What is positive discipline? Positive discipline was created and developed by Alfred Adler and Rudolf Dreikurs, both Austrian psychiatrists who studied human behavior. Adler was a disciple of Freud, later creating individual developmental psychology.

Within this philosophy, they studied childhood and the lifestyles, motivations and beliefs that directly influence how the child will perceive and behave.

Positive Discipline is a program based on these teachings and aims to encourage children and adolescents to become responsible, respectful, resilient and problem-solving skills.

One of the main discoveries of neuroscience is that children are essentially empathic and collaborative, so we can influence this to manifest in their daily lives, using firmness and kindness at the same time, a primordial concept within this philosophy of education. The non-use of punishment and punishment, physical or verbal, is also one of the main pillars of positive discipline.

The error is treated as a learning opportunity and not as something punishable. Another great premise is that adults develop skills to teach directly through example. Positive discipline focuses heavily on solving challenges with the child and not on blaming.

When we start to practice this new look, our beliefs about education change. We were taught that the best way to teach children is to make them feel bad, when the opposite has already been proven to be true: children learn and act collaboratively when they feel good.

Contrary to what you might think, we are not talking about rewarding bad behavior, but working on self-esteem and on the relationship with the child, focusing on solving problems and encouraging them, so that the child is the protagonist of the solution, learning in this way. the skills that are important for your future and for you to develop your sense of acceptance and importance.

When we say that the greatest work is the relationship with the child, this in no way means that we will do everything the child wants or asks of us. It means that the child's gaze will be respected, considered and treated as an important part of that family, contributing to the creation of rules, actively participating in problem solving and learning to understand their own needs and feelings.

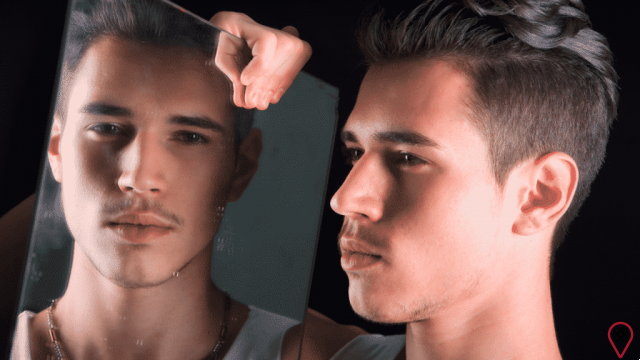

Mutual respect is encouraged, parents become guides rather than bosses. Empathy is learned in practice, as it is practiced daily by parents, as well as self-control. I'm not here advocating that there is a perfect relationship, where screaming and emotional out of control never exist, however, in positive discipline, this becomes the exception and not the rule. Isn't it right that we learn to control our behavior before we want to teach it to children?

Adults are even free to make mistakes and make mistakes great opportunities to do everything better than before. Children's mistakes are generally seen as bad behavior and we need to know how to separate error, emotional overload and bad behavior itself. We can understand the error as something that is done without awareness of the consequence or accidentally, the overload as a moment of great emotional confusion where the child momentarily loses access to the rational part of the brain ("tantrum") and the bad behavior as an action to satisfy a need, but based on mistaken beliefs. The problem is that we treat these three things as manipulation, pampering, teasing, trickery and not as misguided requests for help on the child's part or as a normal part of a developing person. Aggression is natural to human beings, as are all emotions, even those considered bad: sadness, anger, frustration and fear.

What we do in positive discipline is we show in practice acceptable ways to show these emotions, so that children don't harm themselves or other people in doing so. The premise is that when we do not allow these emotions to appear, that is, when we repress these emotions in the child, using threats, punishments and punishments, they do not learn to deal with frustration, fear, anger and sadness. Whereas when we allow these emotions to be shown, but focus our attention on the way they should be shown, those emotions will pass through the child leaving learning.

The main focus becomes the acceptance of the person, but not the behavior. The iceberg of positive discipline is this: bad behavior is just the tip, at the base and underwater are that child's beliefs and needs, that's where parents who practice positive discipline will act.

The phrase “connection before correction” is exactly that: when we work on the relationship with the child or adolescent, we change their beliefs, understand their needs and behavior improves because of it.

It is clear then that positive discipline goes far beyond a set of techniques to make children and adolescents “obey” or to silence their cries. It is also understood that firmness linked to kindness is a viable alternative to authoritarianism, negligence or permissiveness. Positive discipline has more than 50 tools to help us practice firmness + kindness without having to resort to shouting, punishment or threats.

The 4 criteria for an effective discipline

the first criterion for a discipline to be considered effective is kindness and firmness at the same time. It's not about running from one extreme to the other, but being respectful and encouraging while fostering order. It seems difficult, because in general we were educated between authoritarianism and permissiveness, in some cases even negligence. The new scares and brings fear to adults, but the potential for change that this premise brings is immense.

When we manage to convey our expectations and needs as parents in a respectful and firm way, we are showing in practice that it is important to take a stand, but that there are appropriate ways to do so. We put aside the repression of authoritarianism and the excessive freedom of permissive discipline (more on that in later chapters).

the second pillar for effective discipline is to help children and adolescents develop a sense of acceptance and importance. Often, when we want to teach our children through punishments, threats and screams, we are breaking the connection with them without realizing it, in addition to helping them understand that they are bad children, or that the way out is always to get away from the problem, or even that they ARE the problem.

If, on the other hand, we work on this child's connection and sense of importance, we pass on the idea that they are above any misbehavior they practice. It is important to emphasize that fostering a sense of importance is not the same as praising the child. Compliments are part of our expectations, we say “I LIKE your drawing”, while in positive discipline we use encouragement which, in this case, would be “I saw that YOU put a lot of effort into this drawing, I see that YOU are satisfied with it”. The big difference between praising and encouraging is the focus on the process and not on the result, on the effort and not on perfection, on the daily evolution and on the comparison only with yourself, being a great basis for building the connection between the adult and the child, because it promotes the self-importance.

There are many other ways to connect with children. I always ask parents to think about how they connect with their friends or their life partners. They answer me that it is showing their true emotions, being respectful, laughing together, trying to criticize little, not offending the person, acting fairly, encouraging the person to improve through partnership and mutual help, treating that person with consideration and respect, thanking them whenever they do something they think is good, and respectfully asking for help when they need it. And I say that with children this is also how we create connection.

The third and important pillar of effective discipline is to have a long-term effect. We'll talk more about the evils of punishments and punishments… And that's one of the reasons: they don't work in the long run! It is very difficult for a punishment and a punishment to be given only once, on the contrary, when this form of discipline is used, increasing rigidity is always necessary, because the last punishment “no longer takes effect”.

The problem is that increasing the severity of the punishment doesn't work either. Punishment can work to stop a bad behavior, usually because of the fright and fear that the child feels, but it does not bring understanding of how they could have done better, how to do it next time and the reasons that led them to act that way. In other words, punishment does not work to educate, if we understand education as understanding, changes and evolution.

In addition to not bringing positive teachings, punishment has negative results, which we will talk about in the next chapter.

The fourth and final criterion for effective discipline is to teach valuable social and life skills for building good character, which parents define as respect and concern for others, cooperation, responsibility, conflict and problem resolution.

We want our children to be happy, but we also want them to be good for the world and to become good people, as we understand that it will bring meaning to their lives and make their community a better place.

In addition to these reasons, it is known that responsible, conscientious people who have good intra-social skills are more likely to succeed in all areas of their lives.

Permissive, authoritarian and negligent approaches

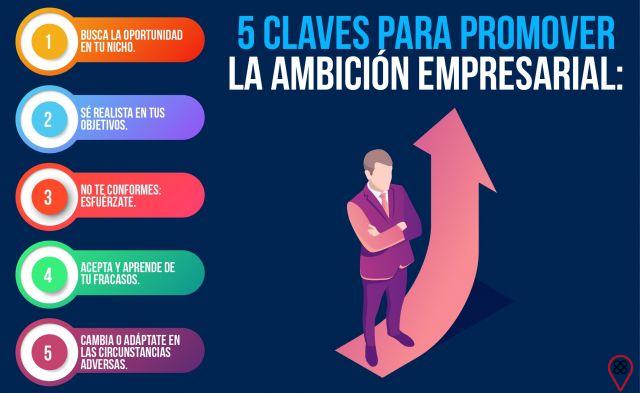

We positioned the disciplinary approaches on two axes, that of firmness X that of kindness, the result is this:

In authoritarianism, or in high firmness + low kindness, we have order without freedom, lack of choices, we have “obey”.

In permissiveness, or low firmness + high kindness, we have freedom without order, unlimited choices and children who do what they want.

In parental neglect, we have low firmness and kindness, it is the worst parenting style because the child and adolescent are aimless, without care, without order and without attachment.

Positive discipline is on the opposite axis of emotional neglect, it is on emotional attachment. It means that we will have order and we will be kind enough to establish that order. The individual choices of children and adolescents are constrained by respect for themselves and others.

The attitude of parents and educators who choose the three approaches is very different: in the authoritarian one, there is excessive control, punishment and rigidity: “these are the rules and this is the punishment you will have if you violate the rules”.

In permissive, there are no rules: “I'm sure we'll love each other, we'll be happy and you'll be able to make your own rules in the future”.

In the negligent, there are no rules, there is not much physical contact and no emotional attachment, much less kindness. There is simply not enough presence for order or freedom to be defined by parents.

In positive discipline, there is emotional attachment (which is different from overprotectiveness): rules are everyone's responsibility and defined together whenever possible, solutions are the focus, and when parents need to use their judgment to decide something, instead aggressiveness and rigidity, they will use gentle firmness. Emotions are accepted and behaviors are the focus of the solution.

About punishments and rewards

We are used to thinking of punishment as a viable alternative to physical punishment. We can define punishments for taking the child out of the environment through command, taking benefits from the child for misbehaving or failing to give something that the child is entitled to, including affection.

Punishments have bad consequences for the child's self-esteem, as explained in the 4 R's of punishment rule:

- Resentment: the child thinks he is being wronged and stops trusting the adult;

- Retaliation: the child thinks about getting revenge and worsens the behavior;

- Rebellion: the child will want to prove that he can do it his own way at all costs;

- Withdrawal: underhanded (lying to get away from punishment) or self-esteem (believing you're a bad person).

In addition, punishment brings what we call the payment cycle: the child feels that he has already paid for what he has done and is free to act again.

Another big problem with punishment is that it makes the child feel that making mistakes is bad and brings feelings of insecurity, shyness and anxiety. The child may also think that if he can't make a mistake, it's better not to start doing anything that could cause the punishment. The problem is that the child still doesn't know how to distinguish what he can or cannot do and ends up being shy in other areas of his life as well.

Punishment teaches the child that he cannot show his feelings, since we do not explain, during a punishment, that it is ok to feel angry, but that what we cannot, for example, is hit a friend. Failure to show feelings in the long term can cause an immense disconnection with you, that is, not knowing how to name what you are feeling and not knowing how to act after feeling it.

Another great harm of punishment is that it does not show the child that we believe he has the potential to do better than what he did. It doesn't convey the message that we believe in them.

Ultimately, punishment has much more to do with dismissing the problem or getting revenge for the child for letting us down or hurting us, than it is with showing the child that he should and could have done differently.

The biggest problem with punishment, whether physical or with punishment, is that it teaches children that those who love also deliberately hurt, that punishment is also a way of showing love. See, I'm not saying that whoever punishes doesn't love, on the contrary, I'm saying that the child can understand that love is suffering (including physical).

Another great harm is that the punishment attaches the consequence directly to the adult who is applying the punishment. When the adult is not around, the child understands that he is free to do the behavior. Punishment does not teach something very important, which is self-regulation.

One of the reasons why children no longer respond to punishment is because models of submission are paved, which is ultimately a good thing: the father is not subject to a lifetime answering to the same boss, the mother is no longer subject to a lifetime being submissive to a man. The child is reluctant to be submissive because basically he does not have a model of submission in his life to look up to.

Times have changed and education has remained the same. Physical or verbal punishment, when recurrent, can cause toxic stress, which is characterized by high levels of the hormones cortisol and adrenaline in the body, with a high chance of serious emotional disorders in the medium and long term.

Finally, punishment does not fulfill its primary objective, which is to make children reflect on their behavior and change it. That's why punishments are, in general, endless cycles.

Regarding rewards, they are the opposite of punishment, that is: they do not teach the child or adolescent to collaborate, participate and understand what they can or cannot do, so when there is no reward, they do not act according to what is expected of them. . Accustoming a child to contribute to activities at home, for example, focusing on rewards, in addition to having the opposite effect (when there is no reward, he will not collaborate), teaches the child that he deserves a gift or a treat for doing what he should do naturally, feeling that it is the right thing to do.

The reward is a certain detachment from reality, for conveying the message that we deserve something when we give something. This is not necessarily the truth!

Neuroscientists have recently discovered that children are naturally empathetic and willing to help as long as we know how to ask. They went further: they found that when children were pleased to have contributed, they lost genuine motivation to help. Children don't need rewards to be collaborative.

Reward doesn't teach a sense of belonging and team, it doesn't teach you to like to collaborate and to do for the common good.

There are over 50 alternatives to punishment and reward in positive discipline. These tools encourage and develop self-assessment, a sense of belonging, collaboration, respect for rules, a focus on resolution and self-responsibility.

Expectations X reality

When I see fathers and mothers in online counseling sessions, I am often told that children are acting badly when, looking at child development, they are doing perfectly natural things for their age.

We are led to build unrealistic expectations about one-year-olds, two-year-olds, babies with undeveloped brains who need our help to calm down, to discover what they are feeling and why. Children challenge, children have emotional overloads (popularly and unfairly known as “tantrums”), children are building their personality and beginning to understand that they are people, that they and their mothers are not just one person.

Many of the problems we have with our children would be avoided if we actually knew what to expect at each age.

A one-year-old cannot manipulate his parents, not in the way they believe he can: their brains just haven't developed the parts they would need to deliberately manipulate us.

Young children have needs and do not have a speech repertoire, or they still do not know how to express what they are feeling. We understand here that needs are not wants: a child has a physical need of hunger and craving for ice cream, for example. That's the difference.

When babies still can't plan how to act when they feel a need, they cry and throw themselves when they get frustrated because they don't understand what they're feeling and don't yet have the tools to show us. The child must always have their needs met, I am not talking about desires here.

Young children have not yet developed the brain capacity to plan how to act, to think directly about more complex causes and effects, they still do not know how to express in words what they want and feel. They simply show their needs the way they can.

It is up to us to understand that children miss, miss encouragement and physical touch, feel afraid of things they still don't understand, feel frustration, anger and still don't know how to show it properly. Adults are responsible for learning to calm down in the face of a situation that upsets them (including "tantrums") and to teach children through their own example, how to act in the face of confused and challenging emotions.

Letter to parents – Change

By now you must be thinking about how to start changing. Every change, from an emotional point of view, has three phases: the phase in which we do things without being aware that it is not the best way, the phase in which we realize that we have done things contrary to what we wanted only after we have done them and the phase in which we realize that we can do things differently, even before actually doing the action.

This third phase is the emotional intelligence phase, where we have control over what we want to change, even if sometimes we do it differently than expected. When this happens, the best thing to do is to understand the reasons for that “slip” and think of solutions so that it does not happen again or that it happens as little as possible. And most importantly, forgive yourself! If we don't think it's right to put blame and shame on our children, we shouldn't do it to ourselves either.

Practicing a discipline so different from what we are used to takes time, it demands effort and will, but an acquired knowledge never returns to the state of unfamiliarity, even though we can return to the old patterns at times.

My message is that our children and teens deserve a respectful education based on connection, not obedience. And that achieving this and raising authentic, conscious and collaborative children is, yes, possible.

It is a great joy and privilege to be able to spread this message of love and respect, I invite you to join me in this endeavor.

Non-Violent Education Article by Thais Basile

We were taught, through the actions of our own caregivers, that tears were a sign of weakness, of exaggeration, of morning. Did you know that tears contain toxic proteins that, when released, allow the emotional to self-regulate again?

As Althea Solter states: “When children cry, the pain has already happened. Crying is not the pain, but the process of stopping the pain.”

All tears are not created equal – there is a difference between angry tears and sad ones. It's sad tears that are behind adaptation and resilience. Sad tears are the ones that cry in response to realizing that something cannot be changed. This is where resilience is born, in realizing that you can survive without getting what you want.

You may also like

- Learn how lack of patience and judgments harm early childhood education

- Reflect: reading is having the freedom to walk wherever you want

- Understand why everything is a matter of education and rethink your way of acting

Angry tears, on the other hand, often cause us to react with anger as well, ignoring the frustration that is driving it and thereby missing an opportunity to turn our anger into tears of sadness, and ultimately, embrace that sadness and pacify the situation.

Facebook: @educacaonaoviolentaporthaisbasile

#nonviolent communication #parenting #education