Dear reader, I believe that you will leave this article bigger than when you arrived here, because I prepared it with great dedication and research, offering educational content of great value. I hope you enjoy.

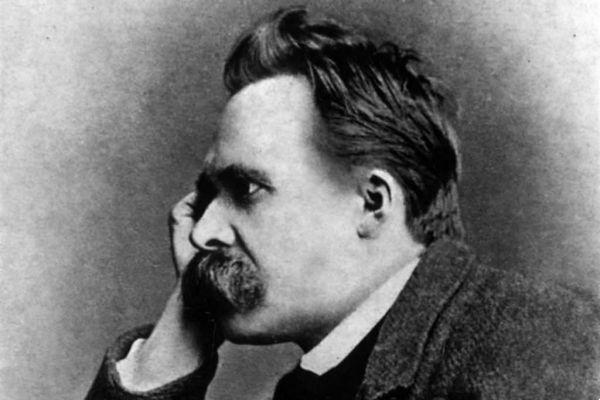

Nietzsche said, in a mixture of praise and lamentation, that Plato, the young Plato, was a kind of poet. And that Socrates, with his authoritative and restricted view of thought, rationality and philosophy, would have been responsible for his misfortune. Perhaps we can see here a kind of collusion between philosophy and literature, whose birth certificate attests and legitimizes, by its ancestry, the point that I will try to develop in this article. It is a matter, albeit briefly and preliminarily, of making some observations that I consider relevant about the relationship between philosophy and literature in Sartre. And I'm going to use two expressions that I borrow from one of Sartre's most relevant commentators, Professor Franklin Leopoldo e Silva. The expressions, which I will have the opportunity to develop them with some leisure, are those of “communicating neighbourhood” and “ethical resonance”. I will use these comprehensive resources of Sartre's thought to basically explore the status of genres (philosophical? literary? philosophical-literary?) in the work of the French thinker, as well as the controversial notion of engagement.

In some way, the question about the relationship between philosophy and literature arises for every philosopher who chooses to resort to these two expressive modalities to present his thought, as is the case of Sartre. Why articulate philosophy and literature in exposing a thought? This may be because philosophy would be insufficient to configure the totality of the human order, whose drama would escape its scope (especially if we consider what philosophy has become since the establishment of the Platonic model, resorting, once again, to Nietzsche's interpretation ). Another way of looking at the issue is that which understands that the philosopher takes refuge in literature to escape, through the concrete, the abstractions of philosophy (in this sense, literary resources, perhaps non-existent in philosophy, would be at the service of the concrete treatment required by the drama of the lived). Or, still, literature would have an auxiliary role for philosophy, operating by the mere exemplification of philosophical theses (in this way, literature would have an auxiliary role in front of the conceptual plot operated by philosophy). Another hypothesis would be the decision to make more accessible to a general public problems whose strictly philosophical treatment would be restricted to technicians and specialists. None of these hypotheses seems sufficient to exhaust this question that permeates Sartre's intellectual experience. However, none of them seem totally outlandish from certain perspectives. To what extent does the problem arise in Sartre's own eyes?

In an interview given at the end of his life, Sartre offers us an answer that is both provocative and disconcerting. everything i wrote, says Sartre, was, at the same time, philosophy and literature. The same Sartre, at another time, as if wanting to confuse his interpreters even more, said that literature was a way of dealing with images and philosophy a way of dealing with concepts. Thus, things are sensibly different. Cristina Diniz Mendonça brings the exact tone of the question: “Philosophy and literature at the same time? Novels as a literary and philosophical form? The works considered 'pure philosophy' as a philosophical-literary form? This Sartrean hybrid is rather an enigma to be deciphered” (MENDONÇA, 2001).

It is necessary to ask any thinker in the history of philosophy a previous question: what is the project that guides and organizes the totality of your philosophical enterprise, even if this sometimes happens in an apparent or superficially dispersed and multifaceted way? In relation to Sartre, this questioning is all the more difficult given the expressive modalities that the philosopher chose to elaborate his reflection: the treatise, the novel, the essay, the biography. And it is in this broad tuning fork that the question of the relationship between philosophy and literature arises for the philosopher. But how to understand the place that fictional work, in the sense of imaginary and not strictly conceptual elaboration, occupies in Sartre's project?

Any reasonably systematic reader of Sartre's work has already asked the question about the status of his literary texts (if not that of the literary status of his philosophical texts). One of the possible answers and, to some extent, quite widespread is the one that claims that literature would keep, for Sartre, a certain relationship of dependence and subordination at the same time that it would serve, to a large extent, to illustrate philosophical theses. It would be, according to this reading, a more concrete way that the philosopher found to make his thought more accessible, sometimes marked by difficulties imposed by the conceptual requirement proper to philosophy.

Certainly, this reasonably restricted view of the situation between philosophy and literature in Sartre has already received, to the point of exhaustion, its necessary relativization: for example, when Thana Mara de Souza reminds us that philosophy and literature present, in Sartre, a relationship of interdependence and would be, in In fact, two distinct but complementary moments in the understanding of the human order.

In Franklin Leopoldo e Silva, this expressive duality gains the status of a “communicating neighbourhood” through which the philosopher says and does not say the same things: “By this we mean that philosophical expression and literary expression are both necessary in Sartre because, through them, he says and does not say the same things” (SILVA, 2004).

To a large extent, as we can already see, this enigma was already present in the philosopher himself. Saying the same distinctly and expressing a difference within this equality because the means by which it is said is not irrelevant to the very constitution of what is said or what is meant by saying.

“Am I a philosopher? Or am I a literate? I think that what I have brought since my first works is a reality that is both: everything I have written is, at the same time, philosophy and literature, not merely juxtaposed, but each given element is at the same time literary and philosophical”. (SARTRE, 1989).

This comment that Sartre dedicates to his own trajectory points us, in the same gesture, to the intrinsic relationship between literary expression and philosophical expression, as much as it requires an effort to precisely assess the status of this kind of hybrid. Or, to be more exact, this unusual communication or “internal passage” that expresses and characterizes the meaning of a “communicating neighbourhood”. A kind of configuration of the relationship between philosophy and literature in Sartre whose notion of passage would be much more significant than that of frontier for its proper understanding. Abandonment of the very idea of border to configure the problem literary-philosophical in Sartre precisely because, “on the contrary, there would be a way to pass from one to the other that would be an internal path, without, in this case, direct communication nullifying the difference”. (SILVA, 2004).

Nor would it be the case to say, in a watertight way, that literature works with images while philosophy is of the order of the concept. This way of dealing with the issue still sounds insufficient. Sartre himself seems ambiguous, or ambivalent, in this respect. When asked why, in his literary manuscripts, there were countless corrections while they were almost non-existent in the philosophical manuscripts, the philosopher said that in philosophy there was only one way to say what one wants, while there are many other ways in literature. However, Sartre himself confessed that he would have abused images in a work such as “Being and Nothingness”. That is, there is still the question of how to equate these two expressive modalities recurrently used by Sartre.

This point of the problem seems to point to two regimes whose schematic formulation we want to enunciate here: the plane of phenomenological (structural) descriptions and the plane of historically narrated experiences. This reading key is fundamental, for example, when we examine the statute of Sartre's capital work, “Being and Nothingness”. An essay in phenomenological ontology in which terms and questions from the philosophical tradition are recovered, but not without operating a kind of twist or subversive reading. There, too, the problem of mixing genres is evident.

Much has been said about the Sartrean appropriation of Husserl's phenomenology. The distance between Sartre and Husserl is often emphasized in this regard, as if the issue were a mere misunderstanding in Sartre's reading of Husserl. Proposing a treatise on phenomenological ontology (a kind of round-square — and the mockery continues in the same tone…), would be the ultimate expression of this misunderstanding. Now, if we are able to understand the status of phenomenology in Husserl (a phenomenology of reason, which is not to be confused with a phenomenology of being), Wouldn't Sartre also be? It seems to me that the central issue is not in this apparently fascinating quarrel with the well-behaved historian of philosophy.

Here, once again, Professor Franklin Leopoldo e Silva opens a key to reading about Sartre's subversive appropriation of phenomenology, that is, one that allows us to realign the relations between the universal and the particular without getting stuck in the respective notions, the most abstract and the most concrete, or even a simple determination of the particular by the universal:

“The description on the plane of the universal is already concrete: this is what differentiates phenomenological ontology from the traditional examination of human nature; and the understanding of individual experiences through fiction only reaches the plane of concrete existence because it inserts the particular existential drama into the universal structure of the being of consciousness: this is what frees Sartrean narration from the traditional novelistic typology in which, for example, the character embodies or explains an essence, which makes the individual remain in the orbit of abstraction (SILVA, 2004).

In other words, it is not a question of understanding the ontologically described structures (actually, an onto-phenomenology) as if they were another name for what tradition called universal, nor, on the other hand, taking the experiences narrated phenomenologically (and historically) as synonymous with the traditional particular or concrete. The reading of Husserl had decisive consequences in the way in which Sartre re-elaborates the philosophical discourse and certainly he saw in the “return to things themselves” the access route to the territory of a concrete approach. However, it is necessary at least to indicate that Husserl and Sartre start from different projects, since Sartre from the beginning censures the orientations of Husserl's thought after the “Logical Investigations”. This new direction is quite different from the first interest that led Sartre to phenomenology when he Raymond Aron, at the bar Le Bec de Gaz, tells Sartre that, being a phenomenologist, “he could do philosophy when talking about his drink” and that “Husserl’s thought responded exactly to Sartre’s expectations” (COOREBYTER, 2000).

The enigma of this hybrid, philosophy and literature, involves the correct understanding of Sartre's appropriation of phenomenology. To claim a treatise on phenomenological ontology, that is, a work for which ontology is not concerned with being as being, but with the “description of the phenomenon of being as it manifests itself” (SARTRE, 1991) means, in the same gesture, if occupy the phenomenal reality and implode with the primacy of knowledge. In such a way that the phenomenon of being becomes somehow accessible to us, through boredom, nausea, the figures of the prisoner of war, the Jew, the woman, the homosexual, all these elements, present in “O ser et the nothing".

In “The Imagination”, a text by the young Sartre, the philosopher evaluates Husserlian phenomenology in the following terms:

“The great event in pre-war philosophy is certainly the publication of the first volume of the “Annual Journal of Philosophy and Phenomenological Research”, which contained Husserl’s main work: “Outline of a pure phenomenology and a phenomenological philosophy”. As much as philosophy, this book was destined to revolutionize psychology.” (SARTRE, 2010).

It will be necessary to broaden the scope of the influence of phenomenology on Sartre's thought. In addition to the avowed role of phenomenology in traditional philosophy and empirical psychology, I think it could be said that it was also destined to revolutionize literature. In what sense? Let us begin to outline this answer from some considerations about Sartre’s essay “A fundamental idea of Husserl’s phenomenology: intentionality”, as well as the recovery of some aspects of the presentation that the philosopher made for the impressive journal Les temps modernes.

In that small text written in 1933, Sartre rebels against French university philosophy, the old French spiritualism, represented by the grandiose figures of its masters and professors: Brunschvicg, Lalande, Meyerson, Bréhier. Sartre characterizes this philosophy as a kind of food philosophy, marked by a spider-spirit that caught and swallowed things in consciousness, now reduced to mere contents. “Nutrition, assimilation. Assimilation, said Lalande, of things to ideas, of ideas between them and of spirits between them. (SARTRE, 2005). This philosophy spoke only the language of epistemology and was, like a Leibnizian monad, with its doors and windows closed to historical reality, which, however, invaded the minds of those young students, anxious to realize philosophy, to make the world of philosophy, for a philosophy that could also speak of the concrete experiences of a world whose historical radicality was lived, in a murky and heavy way, in everyday life in Europe.

These young people clung to a motto indicated in a book by Jean Wahl, “Vers le concret” (“Towards the concrete”). In fact, the direction towards the concrete was still something idealistic and bourgeois. They wanted to start from pure concrete and find the absolute of existence. But they lacked, Sartre confessed, the tools to escape the abstract and outdated language of their masters. Marxism was, in a way, unknown, and it would have taken almost two decades for these young people to make the “second crossing of the Rhine” to find it. There was, however, a first voyage of crossing and discovery, and in it, German phenomenology was found, fully used in the service of contesting the existing university order, a kind of philosophical status quo.

“Against the digestive philosophy of empiriocriticism, neo-Kantianism, against all “psychologism”, Husserl never tires of asserting that things cannot be dissolved in consciousness. You see this tree here — be it. But they see it in the exact place it is: by the side of the road, amid the dust, alone and bent over in the heat, twenty leagues from the Mediterranean coast” (SARTRE, 2005).

Against the French university digestive philosophy, Sartre had found the intentionality of consciousness. This Husserlian concept is the antidote against the course of university philosophy. "All consciousness is consciousness of something." This is the mantra repeated by Sartre's generation. Things are not in consciousness, even by way of representation. They are out in the world, in the midst of things, things between things. Consciousness could not assimilate things, for their natures are absolutely different. Consciousness is an explosion in relation to things, but impossible for them to enter consciousness, since consciousness has no interior. It is pure movement, a kind of wind that heads for things. The world is configured, therefore, in principle, external to consciousness, although relative to it. Consciousness, freed from the security language of the old French spiritualism, is an absolute of existence and not just of knowledge.

“Knowledge or pure “representation” is just one of the possible forms of my consciousness “from” such a tree: I can also love it, fear it, hate it, and this overcoming of consciousness by itself, which we call “intentionality”, reappears in fear, hate and love” (SARTRE, 2005, p. ).

This existential turn of philosophy, provided by phenomenology, finds its correlate in the way in which Sartre sees the work of the writer and the function of literature. Literature, too, can no longer take refuge in the interior life. The writer is inescapably rooted in his time. He is an author who talks about this life, conditioned by the experience of war and, who knows, also of revolution. It is always in a situation, inscribed in a historical reality, which gives it its themes as well as its forms. He can always choose silence or not illuminate certain sectors of reality for the benefit of others, but Sartre says: “The writer is in a situation in his time; every word has resonance. Every silence too” (SARTRE, 1999). It is the refusal of an overflight literature, marked by an ideological conception of art for art's sake. The writer is always and intentionally the writer of his time, a writer in situation, and it is not possible to protect himself in the abstract universality of universal themes because they are immortal. “Immortality is a terrible alibi: it is not easy to live with one foot in the grave and the other out.” (SARTRE, 1999)

The great example taken by Sartre to illustrate this literature of subjectivity as interiority is Marcel Proust. Like the old French spiritualism, Proust also represents an old order now put in check by the conquests of phenomenology and the impositions of its realism. Marked by the analytical method in the attempt to understand the order of the human, Proust can only provide us with an abstract image of concrete experience. “Such is the origin” [the prison of the analytical method], says Sartre, “of the intellectualist psychology of which the works of Proust offer us the most complete example” (SARTRE, 1999).

“Husserl has reinstated horror and wonder in things. He has given us back the world of artists and prophets: frightening, hostile, dangerous, with safe harbors of gift and love. He cleared the way for a new treatise on the passions that would be inspired by that simple truth so deeply unknown to our refined: if we love a woman it is because she is lovely. Here we are freed from Proust. Freed at the same time from the 'inner life'; in vain would we seek, like Amiel, like a child cuddling in her lap, the caresses, the pampering of our intimacy, because after all, everything is outside, everything, even ourselves: outside, in the world, among others. It is not in who knows what withdrawal that we will discover: it is on the road, in the city, in the midst of the crowd, a thing among things, a man among men” (SARTRE, 2005).

Sartre identifies this analytical and interiority spirit in the very way in which Proust's prose is elaborated. For Sartre, Proust would have confused the common condition of man, which is of a metaphysical order (the need to be born, to die, to be finite…) with a human nature. This is how, for example, Proust thinks it is enough, to describe Swann's heterosexual love for Odette, from his own homosexual experience. This identity between heterosexual love, elevated to the status of standard and normality by Proust's society (as well as by ours), and homosexual love, absolutely distinct from that experience, due to its condition of interdiction and marginality, this identification by Proust is only possible because he makes use of this double of interiority and analyticity, embodied in the ideal of a human nature. In the same way, he also uses his bourgeois experience to project that love of Swann for Odette. Proust thus imposes the traits of particularity (his sexual condition, his class origin) to the common condition of men, “he believes in the existence of universal passions whose mechanism would not change appreciably when the sexual character, the social condition, the nation were modified. or the time of the individuals who feel them.” (SARTRE, 1999).

For Sartre, philosophy and literature share a common task: to elucidate and assess the real mediations between the particular and the universal present in the drama of human existence.

Neither traditional philosophy nor the literature of interiority seems sufficient to elaborate this synthesis and this tension. Man always lives the universal as the particular. “Chance does not exist or, at least, not in the way one imagines: the child becomes this or that because he lives the universal as a particular” (SARTRE, 2002). From this perspective, it is up to both the philosopher and the man of letters to experience the contradiction and laceration of trying to overcome the insurmountable heritage of his class and childhood in the elaboration of an adequate portrait of human experience. In the same way that fictional characters fall short when mechanically using a supposed human nature, in the same way real characters, real people are only understood in a rearticulation between the particular and the universal. Who was Paul Valéry?, asks Sartre to his contemporaries. He was a petty bourgeois writer, some will say. Well, not every petty-bourgeois writer was Paul Valéry and this point is the core legacy of Sartre's appropriation of German phenomenology” (SARTRE, 2002).

And it is this rearticulation of the understanding of the universal and the particular (a singular universal) that is at the base of the ideas of “communicating neighborhood” and “internal passage” proposed by Professor Franklin Leopoldo e Silva for the adequate understanding of the statute of the Sartrean work, demanding an expressive modality that is neither just literary nor just philosophical. It is that these varied expressive resources arise, because this is what the characteristics of the human order — neither fully conceptual nor fully imagery — demand, which the philosopher sets out to understand:

“We believe that this would be a way of protecting both the concrete character of the universal and the presence of the universal in the particular. The universal, we know, is not a transcendent entity; and the particular is not the isolated singularity. However, the fact that they are communicators does not imply that the passage alluded to is given: it is a matter of realizing it, and this is a task of historical consciousness, because the human order is historical” (SILVA, 2004).

It is always a question of equating the problem of interiority and exteriority. Or rather, the interiorization of exteriority and the exteriorization of interiority. Literature and history are the privileged stage for the treatment of this dimension. For Sartre, history is full of those occasions when subjectivity finds itself in tension with objective conditions and when it is necessary to decide. Take, for example, the case of the struggle for civil rights in the southern United States in the 50s: the role of Rosa Parks and the achievements of blacks in the state of Alabama.

Around the notion of “ethical resonance”:

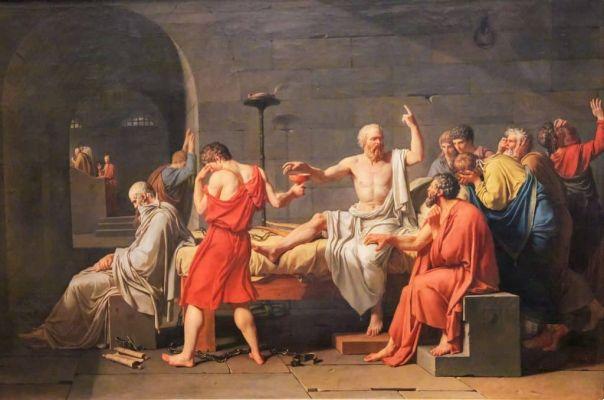

Let us now look at the notion of “ethical resonance”, fundamental for understanding the link between literary expression and philosophical expression in Sartre. At the end of “Being and Nothingness”, Sartre promises an existentialist morality:

“But ontology and existential psychoanalysis (or the spontaneous and empirical application that men have always made of these disciplines) must show the moral agent that he is the being for which values exist. (…). All these questions, which send us back to pure and not complicit reflection, can only be answered in the field of morality. We will dedicate a future work to them” (SARTRE, 1991).

This promised treatise on morality, in a systematic sense, was never made public. What does that mean? The impossibility of presenting an effective existentialist morality? Certainly not. However, the impossibility of systematizing existentialist ethics in a manual or treatise is ongoing, since human reality establishes the value of its action contemporaneously with the choice of a certain action. As they do not have validity prior to effective action (they are values as they are chosen), they cannot appear in a code of conduct either. Hence the presence of ethical issues in practically all of Sartre's texts, constituting what we want to indicate with the use of the notion of “ethical resonance”.

When Sartre, shortly after the publication of “Being and Nothingness”, gives the famous conference “Existentialism is a humanism”, notably an attempt to popularize or make the fundamental theses explored in “O ser e o nada” more accessible to the general public, the presence of the moral theme in that text is surprising. Apparently, this way of exposing his thinking may seem contrasting with the rigid ontological descriptions present in the 1943 work, but why is the simplified and reduced exposition of existential thinking precisely due to the problematization of an existentialist morality? Apparently, I repeat, only laterally present in “Being and Nothingness”?

Here, and once again, the notion of “communicating neighbourhood” (derived from the relationship between philosophy and literature in Sartre) is paired with that of “ethical resonance”, which, in order to sufficiently fulfill the first one, would be able to tie the multifaceted thought of Sartre. According to the interpretation of Professor Franklin Leopoldo e Silva:

“In a more restricted way, it could be said that the ethical problems outlined in 'O ser e o nada' are found again in 'The paths of freedom', and that the way in which they are treated there points to the way in which they will be taken up again. in the 'Critique of Dialectical Reason'. At the same time, studies on Baudelaire and Jean Genet can only be adequately understood if they are treated as concrete approaches to the ethical outlines outlined in general questions about existence, such as bad faith, being-for-itself and being-for-itself. -other. These references must be understood, in the stated terms, in relation to the communicating neighborhood, that is, not as concrete examples of the theory, but as something that points to the (unstable?) balance between the theoretical treatment and the examination of the experiential particularity. The idiot in the family (not finished, it is worth emphasizing) would perhaps indicate the possibility of achieving such a balance: we will never know the result that would have been obtained” (SILVA, 2004).

In order for us to understand the meaning of “ethical resonance” for the relationship between philosophy and literature in Sartre, it is appropriate to address some points present in “What is literature?”, notably because of the concept of engagement.

The first version of Sartre's notion of engagement appears in the presentation of the magazine Les temps modernes. It was about indicating engagement as a requirement of literature and not a mere option or choice among others. In this sense, the opposition between defenders of art for art's sake and those of a party-political literature, such as Soviet realism, does not arise. We are engaged as we are all on board, to use Pascald's expression.

“It is possible to speak of an “ethical resonance” in Sartre’s conception of literature because reader and writer establish an ethical relationship with each other, as literature reveals human freedom and contingencies, even if it presents itself as a necessity in contingency, whether that is to say, it forges the need of the world from its original contingency. Literature pulls things out of their first naivety. Once named and read, no situation can simply be neglected, no one can truly claim to be innocent before the world” (SARTRE, 1948).

But how would this power and reach of literature be able to pull things out of their first naivety and reach the heart of the ethical question? First, it is necessary to remember the distinction that Sartre makes between literature and other forms of artistic expression. No, painting and sculpture do not relate to their object in the same way as literature; there is no parallelism between the arts. Even within literature itself, prose is essentially different from poetry. While the poet deals with words as if they were things, the writer uses them to aim at something that is different to him. He is in search of what it means, in short, he treats words as signs (SARTRE, 1948). For the writer (prose) language is meaning, so only in this case can we speak of engagement or, at least, prose has its own way of being engaged.

Only prose describes and understands human reality, in terms of Sartre's engagement, because only prose deals with words as signs, referring us to something beyond them. The painter, when he paints a picture, does so using paints, strokes, with the intention of creating something; the poet serves words by viewing them as things; but only the writer seeks meaning beyond words, using them as an instrument of his idea (SARTRE, 1948).

It is through a careful examination of the art of writing that Sartre intends to respond to his harshest critics, who precisely refused the notion of engagement: “And since critics condemn me in the name of literature, without ever saying what they mean by it, the best answer to give them is to examine the art of writing, without prejudice.” (SARTRE, 1948). The first point that allows us to speak of engagement in literature (prose) and does not authorize us to extend it to the other arts concerns precisely the notion of meaning. While for prose the word is a sign that refers to signification, in the other arts there is a timid, obscure signification. The word in prose is a means of accessing meaning. Engagement is not required from other arts and artists, at least not the same type of engagement, because only in prose do we take a stand in relation to external things, but only in prose does the word lead us to the outside, so it makes sense to ask the writer's motives.

The significant arts are, like this, the place par excellence of engagement. Let's see: prose, when dealing with signs, makes the relationship between what is written and the world structural, an event that only rarely and in very precise historical conditions can be assumed by the non-signifying arts. It is worth insisting: words for the prose writer are signs (they refer to something outside and different from them); words for the poet, as colors for the painter and sounds for the musician, are things, they are their own meaning, they embody the world instead of addressing it.

In prose, the writer puts form in the background in relation to content. It is not a matter of refusing beauty from prose, but rather that form is always at the service of content. Of course, the writer is also concerned with style, also with form, but the fact that the word in prose is a sign makes all of this refer us to meaning and to the world. Unlike other forms of art in which we are seduced by them, we dwell on them, in prose, the entire structure of the text sends us back to the Universe of meaning. We can always, of course, read a novel paying attention to the form, to the details of the writing. A writer can always write a novel concerned with style over content. However, in these cases, literary art will cease to communicate as prose and the word will become an object, not a sign. The poet is beyond words, the prose writer is beyond them, close to the object; the poet is in a place other than that of communication. (SARTRE, 1948). The prose writer institutes essentiality and necessity in the world, absent by the very contingent structure of reality.

At a certain point in “What is literature?”, Sartre tells us: “How can one expect that the reader's indignation or political enthusiasm will be provoked when, precisely, [the poet] removes him from the human condition and invites him to consider, with God's eyes, language inside out?” (SARTRE, 1948). As we have already said, the poet speaks from outside the language, makes words into things and does not properly establish a communicative relationship with the reader. Prose, on the contrary, mobilizes the reader, encloses him in the human condition. The poet deals with language inside out and the prose writer uses words towards what they mean.

Prose, for Sartre, is the privileged instrument of a certain activity. As the philosopher will say, “the word is a certain particular moment of action and cannot be understood outside of it.” (SARTRE, 1948). Since prose is the privileged element of a certain activity, and since the poet is a disinterested contemplator of words, it is legitimate for the prose writer to ask the reason for his writing.

The prose writer uses words, which are signs, that is, they refer to the world. He names the actions and conducts depriving them of their naivety. And it is this same act of naming that operates an unveiling and unveiling of the world. In other words, the writer acts on the world. If this is so, it is also legitimate to ask which aspect of the world he desires or is concerned with unveiling (SARTRE, 1948). He always directs an interested action on the world. He reveals the world and man to other men and what he wants is for man to assume full responsibility for what is revealed to him. His function, therefore, is to unveil the world and make no one feel innocent before him.

It is still legitimate to ask the writer another question. Why, in his prose, did he concern himself with this or that subject? Why did he decide to illuminate this and not another sector of reality? That is to say, if one speaks with the intention of effecting a change in the world, why this change, not so many others?

The demand for engagement, Sartre will say, is a consequence of the very option to write. “Each one has his reasons: for him, art is an escape; for that, a means of conquering. But one can flee to solitude, to madness, to death; can be conquered by arms”. (SARTRE, 1948). It is precisely the inessentiality of literature, made by the writer his necessity, that Sartre must emphasize. If the act of writing is one option among many others, if the reasons that lead writers to take up their pen and start talking are not necessary events of literature, then it is because literature involves a much deeper ethical choice, hence the demand for engagement that Sartre speaks of. It is the gratuitousness of literature transmuted into necessity by the writer, which fills him with responsibility for every word. Words, Sartre will say, are my sword:

“It is my habit and, therefore, my craft. Long I took my pen for a sword, in the present I know our powerlessness. It doesn't matter: I make and will make books; it's needed; in any case, they always do. Culture doesn't save anything or anyone, it doesn't justify itself either. But it is a product of man: he projects himself into it, recognizes himself in it; only this critical mirror offers its image” (SARTRE, 2007).

There is yet another essential reason for noting this “ethical resonance” of literature in Sartre. This reason is also the one that prevents engagement from being considered an element of the indoctrination of the reader, that engaged literature is synonymous with partisan political literature. This primary motive is that the writer appeals to the reader's freedom, not his passivity. In a sense, writer and reader are a pair, since the activity of writing requires that of reading. A writer cannot be his own reader.

Nowhere is this dialectic more manifest than in the art of writing. For the literary object is a strange top that only exists in motion. To make it appear, a concrete act called reading is needed, and it only lasts as long as this reading can last. (SARTRE, 1948).

It is up to the reader, in this dialectical scheme, to establish the objectivity of the work, in addition to allowing reading, since reading is working with expectations, which the writer cannot have for himself. Reading, that is, the activity of the reader, is the dialectical correlate of writing. Thus, on the writer's side, we have creation and unveiling, while on the reader's side, what emerges is activity and discovery. Thus, reading is a directed creation. In other words, the writer creates the work, but cannot read it; the objective meaning of the work eludes him. The reader, in turn, discovers the work and, in doing so, gives it meaning and objectivity.

“Every literary work is an appeal” (SARTRE, 1948). The writer, when expressing himself through words, appeals to the generosity of the reader. We thus have the engagement of two subjectivities, two freedoms in favor of the dialectical unveiling of the world. The writer is an initiator, he operates an unveiling through language and the reader, through reading. “Thus, the writer appeals to the reader's freedom to collaborate in the production of his work” (SARTRE, 1948). The writer appeals, of course, to the reader's freedom, not his passivity. It is not a question of requesting an alienated freedom, which would jeopardize the production of an absolute end.

“Raskolnikoff, I have already said, would not only be a shadow without the mixture of repulsion and friendship that I have for him and that make him live. But, by a reversal that is proper to the imaginary object, it is not his conduct that provokes my indignation or my esteem, but my indignation, my esteem that give consistency and objectivity to his conduct” (SARTRE, 1948).

That's why the reader is not simply led by the writer, but what you have is a directed creation.

The literary work, like the world, holds an objectivity and reality that do not depend on the reader, since he is not the creator of his ontological reality. However, the reader lends the work a meaning, without which it would be scribbles on paper. Literature is thus an encounter of freedoms, to the point of instituting a dialectical paradox: the more freedom we experience in reading, the more we demand it from the other; the more he demands of us, the more we demand of him. Of course, the writer leads the reader, but as a gentle force that accompanies him from the first to the last page. If the writer imposed passivity on the reader, there would be no reading properly and the relationship between two freedoms would be extinguished. “And conversely, the author's demand is that I raise my demands to the highest degree. Thus, my freedom, when manifested, reveals the freedom of the other” (SARTRE, 1948). Writer and reader, together, commune to achieve the purpose of literature: to recover this world, to show it as it is, but as if it had its origin in human freedom. From this perspective, it is not permissible to think of literature and the writer's engagement, of which Sartre speaks, as indoctrination. On the contrary, it is always an appeal to freedom, for the writer and the reader, and it is not possible to speak of any kind of servitude or manipulation.

Having made these initial and summary notes, it is worth mentioning, although without developing it exhaustively, one last point. The recourse to these expressive modes used by Sartre, therefore, is not a mere option or arising from some writer's talent peculiar to the philosopher, but a requirement, given, on the one hand, the project of understanding and integral elucidation of human and cultural reality. , on the other hand, the dramatic structure and condition of that same reality that only takes effect in history, in the world among men. This peculiarity of the presence of human reality in the world imposes an ethical horizon of commitment on the part of the philosopher and which is also inescapable if we consider how Sartre understands the philosophical or literary word. From the philosopher? Not just the writer? Without wishing to speak like Borges, for whom philosophy seems to figure as a subgenre of literature, we think that, in Sartre, literature and philosophy seem to walk together in the conception of engagement between prose and the person:

“The absolute is Descartes, the man who escapes us because he is dead, who lived in his time, who thought of it day by day with the means he had, who formed his doctrine from a certain stage of the sciences, who knew Gassendi, Caterus and Mersenne, who in his childhood loved a suspicious girl, who fought, who impregnated a maid, who attacked not only the principle of authority in general, but precisely the authority of Aristotle, and who stood in his time, unarmed but not vanquished, like a landmark; what is relative is Cartesianism, that portable philosophy, which moves from century to century and in which everyone finds what they want. It is not by chasing immortality that we will become immortal: we will not be absolute because we have reflected in our works some disembodied principles, empty and null enough to pass from one century to another, but because we fight with passion in our time, because we will have passionately enjoyed it. and because we will have to accept to perish whole with it” (SARTRE, 1999).

But not only that, what would already be an ocean, by the way. This allusion that makes us look at a kind of Descartes in the completeness of a life and a work indicates precisely the always partial apprehension provided by strictly philosophical and conceptual resources, if the human person is its own object. Hence the idea of a work that cannot be explained by life or of a life that is not reduced to the work, but which are mutually required. Hence the incursion into literature, whose resources, although also partial if considered in isolation, share, in Sartre, for the integral understanding of human reality.

The expressive modalities that Sartre used for the elaboration of his thought find their root in the attempt to totalize the order of the human, of the concrete singularity that is the human person - and this is because the analytical and abstract tools rooted in traditional philosophy require, in Sartre's view, a discursive rearticulation whose power points to the comprehensive description of the human, which ends up indicating the very overcoming of that predominantly analytical perspective. In other words, the being whose reality is configured by the paradoxical structure of being in the way of not being and of not being in the way of being requires more than the concept for its progressive and totalizing apprehension. Hence also the value of comprehensive tools “connecting neighborhood”, to try to grasp the terms of the relationship between philosophy and literature in Sartre; and “ethical resonance”, because Sartre's understanding of the human being leads to a situation in the world inescapably circumscribed by the ethical scope and value of his actions. These considerations, therefore, may help us to elucidate this disconcerting interchange between expressive genres and, finally, in the almost proposal of a mixed genre, materialized, albeit unfinished, in the monumental biography of Flaubert.

Emile Bréhier, in his remarks to the Merleau-Ponty conference in 1946, entitled “The primacy of perception and its philosophical consequences”, observed: “I see your ideas expressed in the novel and in painting more than in philosophy. His philosophy ends in the novel” (MERLEAU-PONTY, 2015). Keeping due proportions, and given the familiarity between the philosophies of Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, Bréhier's comment is useful to assess the scope of Sartre's enterprise and which was expressed by the recurrence to different discursive genres, as we try to indicate in this article. . We know that Sartre sought to explore biography in different moments of his intellectual experience and that one dedicated to Flaubert, voluminous and unfinished, seems to crown an always-desired attempt to understand human reality, marked by the suspicion that the traditional philosophical discourse would not be able to effect in all its peculiarities. Hence the idea of “quasi-philosophy” and “quasi-literature” that seems to baffle the reader at first.

The notions of “communicating neighborhood” and “ethical resonance”, as suggested by Franklin Leopoldo e Silva, thus, seek to indicate the “internal passage” between philosophy and literature in Sartre at the same time as pointing out the ethical consequences of Sartre’s and which, most likely, could not have been developed separately, needing to permeate his entire work. An undertaking sometimes misunderstood by those who, like Bréhier, preserve an almost immaculate territory for philosophy.

When encountering Husserl's phenomenology, Sartre was already aware of the need to re-elaborate philosophical discourse and the ethical implications of its approach. It is a requirement that stems from the effort to understand a reality, notably the human reality, which proves to be irreducible to the principle of identity, precisely because it refuses to understand the human person as a being that is what it is. Such an undertaking is at the heart of Sartre's philosophy and required the rearticulation of expressive modalities. We cannot, however, indicate all the characteristics and scope of Sartre's question yet. The decisive role of the Sartrean appropriation of phenomenology seems certain, as an opening for new possibilities of carrying out the philosophical enterprise, which was also noted by Merleau-Ponty: “True philosophy is to relearn to see the world, and in this sense a narrated story can mean the world with as much 'depth' as a philosophical treatise” (MERLEAU-PONTY, 2015). And if this perspective of a double approach seems to contemplate Sartre's first texts, the development of his intellectual experience points to something even more radical: the ethical understanding of the human in a way that the watertight path of pure philosophy and literature may not be able to encompass. . Hence the relevance of the interpretive tools that we try to mobilize in this work.

You may also like

- Who was and what did the German philosopher Hannah Arendt think?

- Do you know what journalism is? come to understand

- Discover the origin and importance of Peripatetic philosophy

Anyway, those who best want to know my academic works can search on Google: Philosopher Nilo Deyson Monteiro.