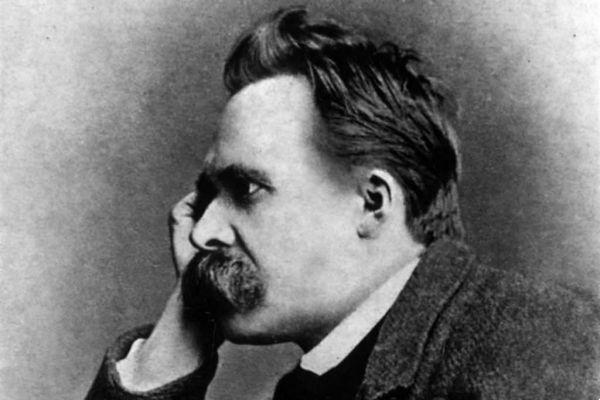

“Become What You Are: Nietzsche and a Philosophical Way of Life”.

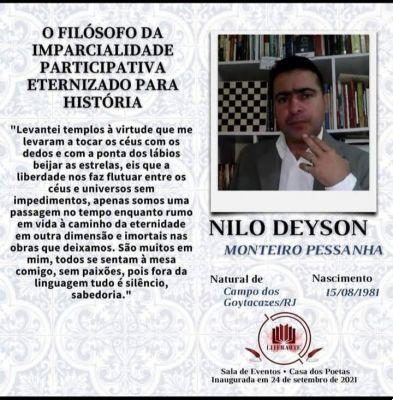

Reader friend, here I prepared a content that will be registered in the portal Eu Sem Fronteiras and I hope you like it. Then read my other articles on Google when you search: “Articles philosopher Nilo Deyson Monteiro”.

Become what you are. This sentence by Pindar, a Greek poet born in the fifth century before our era, was assimilated by Nietzsche as a philosophical principle. Moreover, it was assimilated as a precept of conduct. The German philosopher transformed the statement into a prescriptive truth; in a practical knowledge that serves life, as it is knowledge transformed into a rule of conduct, a precept for action.

In the terms of Michel Foucault (2004), “become what you are” was received by Nietzsche as an ethopoietic knowledge, which means something like a knowledge that produces, modifies, transforms the ethos, the way of being of an individual. . Nietzsche not only learned, meditated and put to the test of life Pindar's sentence, but also, from there, questioned his own conduct, in order to live in accordance with the rule that he voluntarily adopted for himself.

In this article, the idea is to follow this process of assimilation of Pindar's maxim. How did Nietzsche incorporate, transform into a body, the “become what you are”? How did he incarnate, transform into flesh, the simple truth, but difficult to take to the letter, sung by the lyric poet?

I accompany Nietzsche on this journey looking for the same thing he was looking for in the company of the old Greek masters he admired so much: the personal character of the philosopher, the visible marks of his style of living and thinking. This was the proposal made in the essay “Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks”, in which, as he warns in the preface, “doctrines in which the personality of each philosopher resonates most strongly, since, as is usual in textbooks, , the complete enumeration of all the theses that have been transmitted to us only leads to one thing: to the total silence of what is personal” (Nietzsche, 2009).

Here, therefore, I am concerned with the personal character of Nietzsche's philosophy. More precisely, from his exercise of assimilation of a discourse received as true, which directly affects his way of life and directs him towards himself.

A life without examination, without reflection, is not worth living. Of course, young Fritz did not yet know this maxim of Socrates, but he was adept at self-examination. On vacation from school in the summer of 1858, the boy, in his 14th year, wrote his first autobiography, entitled “Of my life”. This adolescent gesture was repeated countless times in decisive moments of the philosopher's life, who sought, through writing and the distanced observation of his emotions, a clarity about himself and about his relationships with the world. A gesture that was repeated until he came to the conclusion that every great philosophy was, and still is, “the personal confession of its author, a kind of involuntary and inadvertent memories” (Nietzsche, 1992).

Nietzsche quotes the sentence of Pindar for the first time, in a work given to the masters of the School of Pforta, known for its austere discipline and the emphasis it gave to the spirit of Greek and Roman antiquity. Nietzsche was an intern at the school from the age of 14 to 20. And, at the end of this preparatory course, he accepted the suggestion of one of his professors and wrote a monograph on the poetry of Theognis, interested not exactly in the theme, but in the possibility of showing his masters that he had mastered the philological technique so dear to Pforta. .

In this course conclusion monograph, Nietzsche quotes the maxim taken from the Pythian Odes, perhaps in its complete form, which says: “Having learned what you are, become as you are” (Nietzsche, quoted by Dias, 2011).

Fritz was taught to be a pastor, like his father who died when he was five, like his paternal and maternal grandfather, like some of his uncles. That the boy would follow in his father's footsteps was the dream of his mother, Franziska, in addition to the expectations of the grandmother and aunts who raised him. After finishing the preparatory course, he left for Bonn, for the Faculty of Theology. And there he lived his student life. The young man closed his books and attacked the piano in improvisations that surprised and enraptured his colleagues in the student brotherhood.

In a few months, Nietzsche tires of bohemian, beer, and nightlife; he also gets tired of pretending to study theology, of pretending to have the faith he didn't have. On the Easter holiday of 1865, he returns to his mother's house and announces to the family that he is going to change colleges. Franziska's world comes crashing down. Family members are called to advise the 21-year-old who rebelled against fate. In June, he writes to his sister who was trying to understand the ongoing revolution:

“It's more difficult to simply accept everything we learn as children, which is seen as true by family circles and which really comforts and uplifts the soul; or is it really more difficult to trace new paths in the fight against custom, in the uncertainty of independent step, but always with the eternal purpose of truth, beauty and good? Does what really matter is to find a conception of God, the world and reconciliation with which one can live with the greatest comfort, or does the real researcher care little about the result of his research? Is the aim of our search for tranquility, peace, happiness? No, just the truth, ugly and scary as it is.

All true faith is inerrant, it provides what the religious person expects to find in it; however it does not offer any argument to demonstrate an objective truth. In this the ways of people are divided; if you want peace of mind and happiness, believe; if you intend to be a disciple of the truth, do your research. Between these two paths there are many compromises. What matters is the main objective […]” (Nietzsche cited by Janz, 2016).

Nietzsche advances in the experience of “become what you are” by taking distance from the destiny programmed by the family. He now knows the path of research, he recognizes himself as a disciple of the truth. Deep down, he knows that what matters is not even the truth, but the search for it; what matters is the path - as the ancient masters said.

And Nietzsche sets out, first researching himself to understand what happened in Bonn. At the end of this school year, he feels ashamed of the dissipated life he has led. His body freezes, rheumatic pains condemn him to bed and rest. He struggles to make amends with this year lost in drinking, concerts, loud and empty colleagues. In a letter sent to a friend he says: “I hope that one day, I can also understand this year from the point of view of memory, as a necessary link in my development” (Nietzsche quoted by Janz, 2016). And he will strive for it; to transform this “so it was” into “so I wanted”. He would later call this life-affirming movement “amor fati”; of all life, including its darkest and most painful aspects.

At the beginning of the following school year, everything changes. Nietzsche flees Bonn and chooses the University of Leipzig to continue his education, now at the Faculty of Philology. On the day of his enrollment there was a celebration of the 100th anniversary of Goethe's entry into the same University. Nietzsche considers this chance a sign of good fortune. And he dedicates himself to philological studies, rigorously, as he learned in Pforta. But without completely abandoning musical compositions, not even the damned philosophy, which reappeared by chance, on a trip to the second-hand bookshop, where he pulled an unknown book from the shelf, by one Arthur Schopenhauer. In recalling this event, he notes:

“I was violently seized by the need for self-knowledge, to the point of self-destruction. For 14 days straight, I forced myself to go to bed only at two in the morning and to get up at exactly six in the morning. I was seized with nervous excitement, and no one knows how foolishly I would have advanced if the temptations of life, vanity, and the obligations imposed by regular studies, had not exerted an opposite effect. . . . (Nietzsche cited by Janz, 2016).

In addition to changing his sleep regimen, the 21-year-old also imposes a strict diet. He turns his room into a cell, and lives in it as an ascetic, in the sense of a type who practices a philosophical or spiritual exercise. We can mock or mock this radical reaction to a simple reading. But the young disciple of truth, without a teacher or guidance, does what he can to experience a truth in his own body. He doesn't just read with his brain and eyes, as we've been taught. Nietzsche reads with his body, because he lets himself be affected by a true statement that needs to be transformed into a precept, a rule of conduct. Knowledge must stimulate the action of itself on itself. And, in the experience of reading Schopenhauer, Nietzsche wants to assess how much he can bear suffering without losing the pleasure of living.

A year after the Schopenhauer event, Pindar's formula will be evoked for the second time, in an article on Diogenes Laertius' sources, published and awarded in 1867. In this second appearance, the “become what you are” is already more ingrained in Nietzsche, who now lives and feels the torment of writing, of the stoning of a style. “The blindfold has been removed from my eyes: for too long I have lived in a stylistic naivete. The categorical imperative: 'You must and must write' kept me awake” (Nietzsche quoted by Janz, 2016).

In another letter, sent to his friend Carl von Gersdorff, during the same period of writing the work on Diogenes Laertius' sources, Nietzsche explains to himself what kind of writing he was looking for: “I need to learn to play on it as on a piano, not, however, studied pieces, but free improvisations, as free as possible, but always logical and beautiful” (Nietzsche cited by Janz, 2016).

Nietzsche's improvisations on the piano were charming and, according to biographer Curt Paul Janz, made a strong impression on listeners, whether initiated into music or not. Gersdorff witnessed Nietzsche's melodic conversation at the piano countless times and, four decades later, still had this small event etched in his memory: “We would meet every night between seven and seven-thirty in the music room. I believe that Beethoven was not capable of improvising more captivatingly than Nietzsche when, for example, a storm was approaching” (Gersdorff quoted by Janz, 2016). Nietzsche's improvisation involved the music's tempo and the moment, captured in a state of mindfulness. We can imagine him at the piano, at the end of the day - the smell of rain, the sudden flashes, the howl of the wind, the rumble of thunder - and Nietzsche there, jumping to the next chord, without hesitation, in the face of the freedom of the moment and of creation.

You may also like

- Practice self-knowledge of your essence

- Enjoy what's best inside you

- Know what to do to achieve the well-being of your soul

In addition to awakening stylistic care and the desire to become a writer, research on Diógenes Laércio's book revealed to Nietzsche what Pierre Hadot and Michel Foucault said in the 1970s-80s: that philosophy, in its origin, was a way of of life, a choice of life. Nietzsche realized that the Greek philosopher taught through his physiognomy, his attitude and his behavior towards others as much as through his speech. The whole doctrine was visible; expressed itself in everyday gestures, in the philosopher's body. The young man realized that the great unity of style - which so fascinated him in the splendor of Greek antiquity - came precisely from this courageous conformity between way of life and thought.

In reading Diogenes Laertius, Nietzsche had access to the minute events in the lives of his philosophical heroes: Heraclitus playing with children, telling those who mocked him that it was better to play with them than to join the scoundrel who ruled the city; Anaximander's solemn robes, his haughty posture, which corresponded exactly to what he said about the tragic character of life. The life of a dog without a master, of Diogenes the cynic… Nietzsche saw with absolute clarity that philosophy was a way of life. And he asked himself: if he took up the call of philosophy, would he be able to live the life of a philosopher? Would you have the courage to live a philosophy, as your heroes of antiquity did?

Nietzsche had to stifle these experiments, these strange ideas, because his academic master and great supporter, Professor Friedrich Ritschl, did not approve of the flirtation between philological science and philosophical adventure. In the professor's eyes, Nietzsche would soon become the greatest German philologist of his time, an authentic scholar. And the student, for reasons of survival, thinking about a future profession, accepted this destiny programmed by his master, who years later will be remembered as “the only genius scholar I have been able to meet” (Nietzsche, 1995).

On the recommendation of Ritschl, Nietzsche was appointed professor of classical philology at the University of Basel shortly after finishing his course. He was exempted from taking the doctoral exam, mandatory at the time to take up a university chair, because of his brilliant academic trajectory. The mother and family, previously fearful of the “little shepherd's” missteps, were excited by the good news. Success, financial stability, the promise of comfort and bourgeois dignity. In the midst of his family, in Naumburg, at the beginning of 1869, Nietzsche felt like a “glorified poodle” and struggled to defend himself from the exaggerated enthusiasm of those who surrounded him and barely understood him.

The night before boarding, Nietzsche retired and, by writing a letter to Gersdorff, tried to clarify for himself this moment of hesitation and hope as well. Once again, Pindar's maxim came to light, now in its negative form: not to become what you are not. Nietzsche (2004), ready to face the world of work — which “holds the reins of each one and knows how to prevent the development of reason, yearnings, the taste for independence” —, assesses the danger it runs and also assesses its own armor. , your own resistance equipment that will be put to the test in this new stage of life:

“The last deadline has expired; the last night I spend in my homeland has come. Tomorrow morning I will leave. […] Yes, yes, it's my turn to be a Philistine. One day or another, here or there, the saying always comes true. Functions and dignities are things that are never accepted with impunity. The whole problem lies in knowing whether the chains are iron or line. I still have enough courage to break, if necessary, any link and start anew in another way or in another place, a new life. I have not yet acquired the stooped posture so characteristic of the teacher. Zeus and all the muses preserve me from being a Philistine, man abandoned by the muses, man of the flock! I don't see how I can become what I'm not. […] But I imagine that I can accept the danger more calmly than most philologists: philosophical seriousness is very deeply rooted in me. The real and essential problems have always been shown to me by the great mystagogue Schopenhauer, so that I do not run the risk of deviating dishonorably from the “Idea”. To inject this new blood into my science, to communicate to my listeners that Schopenhauerian seriousness, which shines on the forehead of the sublime man, this is my vote, my audacious hope [...]” (Nietzsche apud Dias, 1991).

On April 19, 1869, at the age of 24, Nietzsche arrives in the Swiss city, which will witness, over the course of a decade, the painful birth of a philosopher.

Reader friend, you may have noticed that this article I prepared with references exactly so that you can research these references and know it right, so pay attention to the development. Come with Nilo Deyson.

The beginning of the young teacher's pedagogical activities coincides with the consolidation of his friendship with the musician Richard Wagner, who lived at that time in a corner near Basel, on the edge of the Lake of the Four Cantons. Tribschen became Nietzsche's spiritual homeland for three years. In a letter to his friend Erwin Rohde, he sends news of the time:

“In recent times (September 1869) I have been to Tribschen four times in a row in a short space of time, and besides, a letter goes the same way almost weekly. Dear friend, what I learn and see there, what I hear, is impossible to describe. Schopenhauer and Goethe, Pindar and Aeschylus did not die […]” (Nietzsche quoted by Dias, 1991).

If, on the one hand, “The Birth of Tragedy”, Nietzsche’s debut book published in 1872, records the philosophical and aesthetic experiences shared with Wagner and his wife Cosima, loved by Nietzsche in secret, on the other hand, in the lectures and writings on education, Nietzsche reflects on his own craft, which includes a critical look at educational institutions and the “mass culture” of the time, embodied in the figure of the philistine of culture.

The third quote from “become what you are” — the first published in a book — appears in this field of reflection linked to the role of the educator, to the criticism of utilitarian culture, criticism of the philistines who submitted culture to the laws that govern the Comercial relations. And this time, Pindar's verse was incorporated into the text in its imperative form. This is how it appears in the first paragraph of Schopenhauer educator, the third of the “Extemporaneous Considerations”:

“On being asked what nature found in men everywhere, the traveler who has seen many countries and peoples and many continents replied: they have a propensity for laziness. Some will think that he would have answered more justly and correctly: they are all timid. They hide behind customs and opinions. Deep down, every man knows very well that he only lives once in the world, in the condition of uniqueness, and that no chance, however strange, will combine for the second time such a diverse multiplicity in this unique whole that he is: he he knows it, but hides it as if he has remorse in his conscience—why? For fear of the neighbor who demands this convention and hides in it. But what compels the individual to fear his neighbor, to think and act like a herd animal and not rejoice in himself? In some very rare, perhaps modesty. But in most individuals it is indolence, self-indulgence, in short, this propensity to laziness of which the traveler spoke. He is right: men are even more lazy than timid and fear first of all the annoyances that would be imposed on them by absolute honesty and nakedness. Only artists hate this negligent walk, with measured steps, borrowed ways and false opinions, and they reveal the secret, the bad conscience of each one, the principle according to which every man is an unrepeatable miracle. When the great thinker despises men, it is their laziness that he despises, for it is this that gives them the indifferent behavior of mass-produced goods, unworthy of contact and teaching. The man who does not want to belong to the crowd need only stop being self-indulgent; let him follow his conscience which cries out to him: 'Be yourself! You are not what you now do, think and desire' […]” (Nietzsche, 2003).

I understand those who consider such a speech banal, conventional; something that any literate coach, motivational speaker or personal trainer of self-knowledge could use to sell, once again, the well-known formula: “Be yourself!”. But this current meaning is different from the one that guided Nietzsche's thinking. The “be yourself” of the entrepreneurial and productive type assumes that there is a true, inner, essential self, which for one reason or another does not take risks in the trade of life. Common sense says that, in order to find this true self, it is necessary to know oneself, in the sense of diving into an interiority in order to establish a positive relationship with oneself and obedient to the sacred laws of any religious dogma, or to the laws of the world. market, as it is today. Nietzsche was not adept at this kind of self-practice. I quote another passage from Schopenhauer educator:

“But how do we find ourselves? How can man know himself? It is something obscure and veiled; and if the hare has seven skins, a man may well shed seventy times the seven skins. But not even then could I say: 'Ah! Finally, here is what you truly are, there is no longer the covering'. It is also a painful and dangerous undertaking to dig in one's self and descend by force, by the shortest path, to the depths of one's being. How easily, then, does he risk being injured so grievously that no physician could heal him. And, furthermore, why would this be necessary, if everything bears the witness of what we are? Our friendships and our hatreds, our gaze and the shaking of our hands, our memory and our forgetfulness, our books and the traces of our pen? […]” (Nietzsche, 2003).

Despite being intimate with solitude and silence, the philosopher knew the role of the other in the process of constituting himself. His voluminous correspondence, the practice of forming small groups of friends dedicated to research, knowing that it serves life, show that the self-examination practiced by Nietzsche had nothing to do with a narcissistic journey, or even with a confession of himself, aiming at a better adaptation to the laws of the commerce of life. He was attentive to this “everything” that crosses the subject and that carried the testimony of what he was.

The true self, at that time when Schopenhauer writes as an educator, would be outside the subject, beyond him, above him. For this reason, in the philosophical exercise that Nietzsche proposes to young individuals, the master's otherness is fundamental in this journey towards himself:

Let the young soul look back on his life and ask the following question: 'What have you truly loved until now, what things have attracted you, what have you felt dominated by? Make the entire series of these venerated objects pass before your eyes again, and perhaps they will reveal to you, by their nature and succession, a law, the fundamental law of your true self. Compare these objects, observe how they complete each other, grow, surpass each other, transfigure each other, as they form a graduated ladder through which you have so far risen to your self. For your true essence is not hidden deep within you, but placed infinitely above you, or at least what you commonly take to be your self.' […]” (Nietzsche, 2003).

We can call this type of examination aimed at the constitution of a self an “exercise of admiration”, to use the beautiful expression cut by Cioran. It is about meditating, slowly contemplating the figures we admire for having accomplished things we would never do out of indolence, lack of strength, fear or for any other reason. These admirable figures, with whom we have an affinity, would form a kind of “constellation” that would guide us towards ourselves, through imitation. As Charles Andler explains:

“Our imitation will always be original. The successive and ever higher models that we will propose to venerate them will teach us only the law of our individuality. The series of our successive admirations is an indication of our temperament. It is a light that precedes us on the path we open for ourselves […]” (Andler, 2016).

How does one become what he is? At the time when he wrote the “Extemporaneous Considerations” (1873-1876), Nietzsche enthusiastically bet on the “metaphysics of the artist”, on the figure of the genius, on the rare subjects that give character to an era; an idea that he learned from Schopenhauer and that he projected onto the figure of Wagner. In a world without God, man elevates himself looking at artists, poets, especially the poets of music. The fourth of the “Extemporaneous” is a text in homage to Wagner, a tribute to the theater built by him, Bayreuth, which Nietzsche saw as the beginning of the Renaissance of the Greek spirit in Germany; the starting point for the creation of a new type of man, the man of the future, enhanced by the Master's art.

The young Nietzsche saw in the Wagnerian musical drama the possibility of a revolution; not a social revolution, of taking power over the State or the means of production, but a revolution in the soul of each individual. He imagined that the figure of the great artist could affect the public, snatch it with new questions, below or beyond those circulating in the cultural and educational institutions of his time.

Nietzsche projected a cultural revolution, a transformation of all culture, of all ways of being and thinking in modernity, which, in short, had as its goal the constitution of “ordinary men” and, as a principle, the “union of intelligence with the property". Something that in our neoliberal era has become more evident and effective.

“The real task of culture would then be to create men as 'current' as possible, in the sense in which one speaks of a 'currency'. The more there were ordinary men, the happier a people would be; and the purpose of contemporary educational institutions could only be to make each one progress as far as his nature calls him to become 'current', to form individuals in such a way that, from his level of knowledge and knowledge, he can extract the greatest amount of happiness and profit. Each should accurately assess himself, each should know how much he could expect from life. 'The union of intelligence and property', which stands as a principle in this conception of the world, takes on the value of a moral requirement. From this perspective, one even hates any culture that makes one lonely, that proposes ends beyond money and gain, or that demands a lot of time; here, it is customary to discard divergent tendencies, which appeal to a 'higher egoism' or a 'moral epicureanism of culture'. The morality that is in force here surely demands something of the opposite, in big money, a fast culture, so that one could quickly become a being that earns money, but also a very grounded culture, so that one could become a being that makes money. earns a lot of money […]” (Nietzsche, 2003).

In this period in which he writes and publishes the “Extemporaneous Considerations”, Professor Nietzsche, now in his 30s, chooses the market and the State as the main obstacles for a young individuality to become what he is. The “businessmen's selfishness” wants to produce only anxious consumers of culture, fashion, and entertainment.

Nietzsche realizes that the happiness of the herd would turn into big business. The business of public opinion that will profoundly affect people's way of being, something that the Frankfurt School would later call the “cultural industry”, today metamorphosed into “social networks”.

On the other hand, the teacher lays bare the “egoism of the State” which, through its educational institutions, only intends to form obedient, useful and disciplined servants. A type of people who do not need to have faith in the State, as if it were the “march of God in the world”, as Hegel thought, but who were obedient enough to work for it, even against their will, even if they were stupefied by drugs or convinced of the uselessness of all personal effort. A type of people who complain, who have fits of indignation against the rulers on duty, but without the firm determination to abandon the career of the State, because it guarantees comfort and the possibilities of consumption. And it also takes up time, fills the day with obligations, chatter and demands that make the silence and emptiness necessary to return to oneself and contemplate those lights that precede the path impossible.

The market and the modern state do not need mature men who play, like Heraclitus. The rush is general, says Nietzsche (2003), “because each one quickly flees from himself”. And in this speed of flight from self in favor of good employment, profit, the dignities of consumer power, there is no time for young souls to mature, because idleness without laziness is considered a crime against the market, a useless luxury for the hyperactive society. “Some birds are blinded so that they can sing better: I do not believe that men today sing better than their grandparents, but I know that they are blinded very early” (Nietzsche, 2003).

Nietzsche claims that modern men are blinded by a light that is too bright, too sudden, too variable (Nietzsche, 2003). It is irresistible to think, nowadays, of the light of smartphones as the needle that blinds us and prepares us for self-denial and obedience to the laws of the market, competition and public opinion. A type of light that passes through our eyes daily, that occupies us, makes us anxious for news and news that do not change our way of being, because information is not wisdom. A light that makes our escape from ourselves even faster because we are encouraged to comment, judge and control the lives of others; the life of everyone and anyone who is not above us, who does not have the power to elevate us. And, in this distraction, in this vigilance that entertains and amuses, between one like and another, between one sealing sentence and another, we distance ourselves from ourselves, we distance ourselves from the examination of the self, from the reflection on what we truly love one day and that can contain the path to our own elevation:

“O poor devils in the great cities of world politics, young men, gifted, martyred by ambition, who consider it their duty, at all events — and something always happens — to bring your comment! Which, thus making dust and noise, believe it to be the car of history! That, by always watching, always paying attention to the moment to insert your comment, they lose all authentic productivity! Even if they yearn a lot to do great works, the deep silence of pregnancy never comes to them! The event of the day pushes them around like straw, while they think they push the event – the poor things! […]” (Nietzsche, 2004).

During the ten years of teaching, the professor, in his own way and with the resources he had, tried to introduce young people to the great masters of antiquity and philosophy that could free them from the current of the market and the State, agents of the poor. More than the lesson plans or academic reports presented to the University, it is interesting here to recall the testimony of a former student of Nietzsche, Louis Kelterborn. Perceiving, through his eyes, the teacher's way of teaching. His behavior, his posture, his way of being that inspired young individualities.

“His way of addressing students was absolutely new to us and awakened in us a sense of our own personality. From the beginning, he knew how to stimulate us to have a greater interest in study, perhaps even more indirectly, through his knowledge and example, than directly, by declaring to us, for example, that every man should at least once in his life to take the trouble to devote an entire year to study, turning night into day, and that year had arrived for us. He did not regard us as a group, as a class or a herd, but as young individuals. One of his main goals was to stimulate us to a personal activity […]” (Louis Kelterborn quoted by Dias, 1991).

Basically, this testimony reveals how Pindar's sentence was transformed into a rule of conduct and conduct for the arrival:

“During the conversation, the teacher tried to listen more than talk; through questions, he encouraged his interlocutor to express his opinions freely. But what particularly united me to him was his essentially musical temperament. Most of our conversations revolved around musical matters, at the center of which shone the star of Richard Wagner. From the first visit he had confided in me that he had once hesitated, like myself, to devote himself entirely to music, that he had deepened his musical knowledge with the utmost seriousness, and that he had sought information not from modern manuals but from ancient sources, from where our classical masters had taken their knowledge […]” (Louis Kelterborn quoted by Dias, 1991).

The tension between the teacher's life and the philosophical life, between the profession and the vocation, intensifies from the writing of Schopenhauer educator, a text of long gestation, delivered in its definitive form in August/September 1874. Two weeks later send the originals to the printer, Nietzsche writes to a friend:

“This final part of our summer semester was a difficult time. In addition to all the other works, I had to rewrite a long passage of my third “Consideration”, and the inevitable emotional upheaval caused by reflections and probings inside many times almost knocked me down, and even now I was not able to completely get out of the puerperium […] ” (Nietzsche apud Janz, 2016).

The recovery from childbirth was difficult and slow because, in this writing, Nietzsche (1995) outlines his most intimate history, his becoming, as he will say in “Ecce homo”. From Schopenhauer onwards, Nietzsche idealizes the figure of the philosopher or, more precisely, idealizes the heroism of a philosophical life. He emphasizes the courage needed to walk away from the desires of the crowd, the morals of the herd, and the temptations of fame. It is a lonely and dangerous life. Dangerous because the true philosopher fights against his time, not paying lip service to the political theater, but fighting in himself the “spirit” of his time, an “impure and confused mixture of incompatible elements forever irreconcilable” ( Nietzsche, 2003). A jumble, a confusion of principles and statements that condemns the individual to the daily exercise of hypocrisy in the relationship with the other and with himself, because half-truths only produce relationships in half. There is no way to be honest.

Nietzsche's thought soared, he frequented the heights of the ideal, the rarefied air of philosophical genius, but when he laid eyes on his desk, he had a pile of schoolwork to correct, he had classes to prepare, he had to deal with the of philological science, he had social obligations that demanded his time and attention. Nietzsche was not a free man. Only with a strong dose of hypocrisy could he answer “yes” to that barbaric question he asked: “In the depths of your heart, do you say 'yes' to your existence?” (Nietzsche, 2003).

This tension between academic life and philosophical life grows and overflows, reaching Nietzsche's body. The regiment of the disease was established at the end of 1874. The attacks of headache, accompanied by attacks of vomiting, would become more frequent. Nietzsche reports in letters the state of his health, which deteriorates over time and with failed attempts at treatment, as the doctors consulted are unable to reach a diagnosis.

In addition to the tension between academic life and philosophical life, something changes in Nietzsche's constellation. He feels that his passion for Wagner is gone. All that ardent militancy for the Revolution of man through Wagnerian musical drama now seemed to him a mistake, perhaps foolishness. “I had seen the sublime, the ideal — this is what I came to Bayreuth with, hence my disappointment” (Nietzsche quoted by Janz, 2016).

On the way to becoming what one is, Nietzsche feels that he has reached a higher point of view on art and on life. His research took him beyond the limits of romanticism and idealism that animated Wagner's cultural and aesthetic project and Schopenhauer's philosophy. It was necessary to explore this deviation, this misdirection that opened up to thought, despite the limitations imposed by illness and the sadness born of a great disappointment. Both body and soul suffered, and Nietzsche needed to write to heal.

Unable to read and take notes because of eye pain and migraine attacks, the philosopher dictated the book “Human, too human”, a work understood as his declaration of intellectual independence. “In it I delimited for the first time the contours of my own thought” (Nietzsche, 2005). In this book, he also found a suitable form for his improvisations: the aphorismatic style, very free. Some sentences spanned two or three lines, others spanned entire pages. Themes thought and repeated, in long walks (when health allowed), took shape in the voice and became texts by the work and diligence of friend and former student Heinrich Köselitz. “I dictated, my head bandaged and aching, he wrote, and he also corrected—he was, at heart, the real writer; I was just the author” (Nietzsche, 1995). In “Ecce homo”, the philosopher will recall those painful months and will express his gratitude to the illness that forced him to return to himself:

At that time, my instinct was inflexible to put an end to that giving in, following, being confused with others. Any kind of life, the most unfavorable conditions, illness, poverty—everything seemed to me preferable to that unworthy “lack of self” into which I had fallen out of ignorance, out of youth, and into which I had subsequently remained out of lethargy, out of the so-called “feeling of self-doubt”. to owe". […] The disease slowly freed me: it spared me any rupture, any violent and shocking step. Illness gave me the right to a complete reversal of my habits; she allowed, she ordered me to forget; she presented me with the obligation to be still, to be idle, to wait and be patient…

“But that means thinking!… Only my eyes put an end to bibliophagy, read “philology”: I was saved from books. That innermost Self, almost buried, almost muted under the constant imposition of listening to other Selves (―this means reading!), woke up slowly, timidly, hesitantly ―but finally spoke again. I have never been so happy with myself as in the sickest and most painful times of my life: just look at Aurora, or the “Wanderer and his shadow”, to understand what this “return to me” was: a supreme kind of cure! […]” (Nietzsche, 1995).

Illness will finally free Nietzsche from academic life. She will force you to resign. On June 30, 1879, the resignation of Professor Friedrich Nietzsche was recorded at the University of Basel. Moved by a feeling of gratitude and affection, the University councilors granted the professor a pension equivalent to two thirds of his salary. With that money, Nietzsche modestly lived a wandering life, always looking for a heaven conducive to his thoughts: summers in the heights, usually in the Sils-Maria region; winters in the south, on the French or Italian riviera. Aside from ordinary expenses, Nietzsche's only luxury: his books. He financed the printing of all his books, which sold little, some of them with very low circulation, practically destined for a small circle of friends.

Nietzsche exercised perseverance in those 10 years in which he lived the life of a walking and solitary philosopher. From 1878 to 1889, the year of the spiritual collapse in Turin, he wrote ten books. Pindar's sentence will be remembered on this journey. In “Human, too human”, originally published in 1878, it appears in aphorism 263. In “The gay science” (1882), in aphorisms 270 and 335. In “Zarathustra”, a work created between 1883 and 1885, Pindar's phrase comes back in two passages: "The convalescent" and "The offering of honey." In “Ecce homo”, an autobiography written three months before madness manifested itself in Turin, the maxim will return as the subtitle of the work. A kind of crowning of a path.

In this text, the philosopher will make his final reflection on the utterance transformed into a philosophical principle and life experience. This is what Nietzsche said:

“At this point there is no longer any way to evade the answer to the question of how one becomes what one is. And with that I touch on the ultimate work of the art of self-preservation ― of self-love… […] That someone becomes what he is presupposes that he does not even remotely suspect what he is. From this point of view, even the mistakes of life, the momentary deviations and secondary roads, the postponements, the “modesties”, the seriousness wasted in tasks that are beyond the task, have their own meaning and value. […] However, the organizing “idea”, destined to dominate, continues to grow in the depths – it begins to give orders, slowly leads back from the detours and secondary roads, prepares isolated qualities and capacities that one day will prove indispensable to the whole. — It builds up one after another the auxiliary faculties, before revealing something about the dominant task, about “end”, “goal”, “meaning”. “Faced this way, my life is simply miraculous. For the task of transvaluing values, perhaps more faculties were needed than ever existed in a single individual. Hierarchy of faculties; distance; the art of separating without incompatibility; nothing to mix, nothing to “reconcile”; an immense multiplicity, which, however, is the opposite of chaos – this was the precondition, the long and secret working and art of my instinct […]” (Nietzsche, 1995).

“Become what you are – without even remotely knowing what you are”. Nietzsche lived the sentence so intensely that he ended up renewing the sense of the old truth from his own experience. What would it be like to become what you are without knowing what you are? Experimenting, trying, rehearsing, in that sense so well cut by Foucault (1984) in the introduction to “The use of pleasures”: “The essay as a modifying experience of the self in the game of truth is the living body of philosophy, if at least it it is still today what it used to be, that is, an asceticism, an exercise of oneself, in thought” (p.13).

It is about understanding the philosophical life as an experimental life. “We want to examine our experiences as rigorously as a scientific experiment is carried out, hour by hour and day by day! We want to be our experiments and our guinea pigs” (Nietzsche, 2001). Here, you don't look so much upwards, to the stars that illuminate a path. The look is on the chaos that the philosopher carries within himself. A multiplicity of forces in a permanent state of tension and expansion. And out of that chaos a dancing star jumps. A way of life, another possibility to live a life faithful to the land and true to oneself.

At this moment in which we are seduced by identity politics as a form of resistance to the populist wave, it may be interesting to recall the Nietzschean lesson of becoming what one is without knowing what one is. It is not about assuming and fighting and even dying for an identity, for a crystallized way of being, which demands their rights and their recognition by the State or society. Perhaps it is possible to go further in this struggle against populist politics which, as Peter Sloterdijk (2004) thinks, only takes place when there are concrete conditions to demean the strange, the other, the different.

The fundamental question that Nietzsche poses seems to me to be linked to that evil question one day formulated by Foucault (2000): “How not to be governed? How not to be governed in this way, in the name of these principles, in view of such objectives and by means of such procedures; not in this way, not for this, not for these people?”

Nietzsche's experimentation, in the final analysis, is becoming another, an exercise in otherness; of transposition, of transformation of what one is through reflection, study, contemplation and the invention of ways of life, of new possibilities of life, based on other values and principles. We could characterize Nietzsche as the discoverer of heteronarcissism, as defined by Peter Sloterdijk (2004), because what the experimenting philosopher “affirms in himself are the others, the alterities that enter him forming a composition that crosses him, enchants him, tortures him and surprises him. Unsurprisingly, life would be a mistake.” A mistake, because, as targets identified, located, manipulated by populist politics, we would only feed the monster we thought we were fighting. Anyway, if you want to read other articles by Nilo Deyson, just go to Google and search: “Articles Nilo Deyson”.

Contacts for lectures and others:

- Email: dyson.11.monteiro@hotmail.com

- Tel: (22) 999402903

- Facebook: Nilo Deyson Monteiro Pessanha

- Fanpage: Philosopher Nilo Deyson Monteiro

- Instagram: Nilo-Deyson-Monteiro

- I am a philosopher, writer, poet, columnist and speaker.

- Founder of the philosophy of participatory impartiality.

- Author of the philosophy book “All the Hearts of the World”.

- We also participate in anthologies and periodicals.

- I am an immortal academic at the Academia Pedralva Letters and Arts, occupying chair number 17. Founding member of the Italian Academic Nucleus di Scienze di, Littere e Arti, among other institutions.

- On Google: Philosopher Nilo Deyson Monteiro

Nilo Deyson Monteiro Pessanha