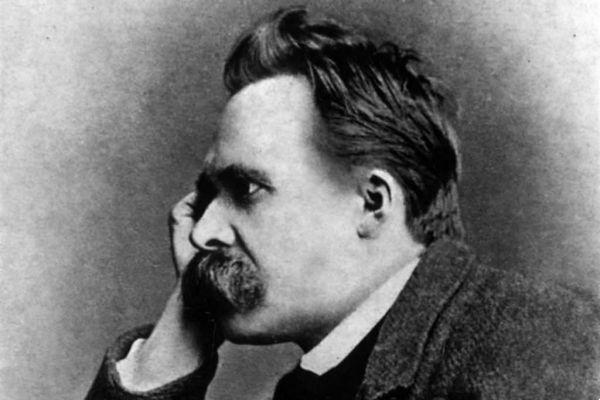

Hello guys! Today's text has as its theme: “Nietzsche and the 'deification of the devil': A project to “overcome morality”.

In this article, I take as a starting point the idea that the critical procedure of genealogy ends up acting as a pragmatic strategy for the dissolution of the most basic structures of comprehensibility of Western-Christian culture. The objective here is to demonstrate that much of Nietzsche's criticism of the process of moralizing impulses is confirmed as a true transformation of understandability. In this context, although Nietzsche's genealogy can be understood as just one of many interpretations, its differential lies in its ability to displace thought structures and be able, for example, to understand that the value of the world is in our interpretation [ …], that every elevation of man brings with it the overcoming of narrower interpretations, that every strengthening achieved and every expansion of power opens new perspectives and makes us believe in new horizons — this runs through my writings. The world, which matters to us in some way, is false, that is, it is not a fact, but a composition (Ausdichtung) and rounding (Rundung) on a meager sum of observations. The world is 'in flux', as something that comes into being, as a falsity that always moves again, that never approaches the truth - for there is no truth (FP 1885 2 [108]).

“It is this constant detachment of perspectives that opens a new horizon of possibilities for man, whether in the different treatment of his affections or in his potential for the future. It is not just a history of morals or even the identification of values of decadence that appears as the focus of Nietzsche's genealogy, because, as an experience and experience, it must not only diagnose, but in the exercise of this task, also cultivate greatness to act. as inspiration and promise of 'more future'” (GM II 25).

With this shift in perspectives in mind, I use one of Nietzsche's writing plans as a discursive guide to debate these new possibilities and overcomings. Specifically, your project of:

“Overcoming morals.

[For] hitherto man has kept himself miserable, insofar as he has treated in a perfidious and slanderous manner the impulses which were most dangerous to him, while at the same time he has slavishly flattered the impulses which preserved him.Conquest of new powers and countries:

a) the will to untruth

b) the will to cruelty

c) the desire for voluptuousness

d) the will to power” [VCS] (FP 1885 1[84]).

Following this script, four sections are laid out below that, in the sense of this search for “new powers”, will present their genealogy as a strategy of “overcoming morals”, or rather, as a reflection of the corruption of those dangerous affections vilified by the dominant moral. It is a true exercise of spiritualization and living of that ancient thesis that states that “for too long, man has considered his natural propensities with 'bad eyes', in such a way that they have joined him with 'bad conscience'. A reverse attempt is in itself possible—but who is strong enough for that?” (GC 24).

Looking at this “reverse attempt”, I bring to the debate in item 1, “The will to untruth: from truth to (great) health”, the idea that the process of developing genealogical research is the result of a historical critique that, taken to its ultimate consequences, finds in the change from truth to health one of the main tools of its criticism. Subsequently, in “The Will to Cruelty: Nietzsche and his 'war machine'”, I present a debate about the tortuous and uncertain limits between the bellicose rhetoric of Nietzsche's text and his demand for the spiritualization of these themes. In my view, the process of moral detachment from his criticism inevitably passes through the human's ability to deal - with good conscience - with immoral affections such as cruelty and violence. In item 3, “The desire for voluptuousness: sensuality vs. moral modesty”, I identify another mandatory point of the strategic distance that prescribes a pathos of distance to the whole perspective of moral modesty and the mortification of the body that was made famous in the priestly perspective. -Christian. Finally, in “'The will to power' as the cultivation of greatness”, I defend the hypothesis that an integral part of his project of distancing from sick morals can be identified in the debate related to the cultivation of greatness, namely, in the identification and stimulus of an instinctual economy focused on the great, for a type “more worthy of life, more certain of the future” (AC 3).

“The will to untruth”: from truth to (great) health:

Following the diagnosis of Nietzsche's genealogy, it is noted that the question of the truth of a given discourse is gradually being replaced by a “will to health”. This change of perspective is one of the central points of his “overcoming morality” (FP 1885 1[84]), a turning point in his philosophical critique that implies not only the identification of problems related to the values cultivated by decadent modernity, but also in the recognition of a whole new form of comprehensibility.

In fact, the basis of this transfiguration of comprehensibility has already been demonstrated in aphorism 12 of the third dissertation of “To the genealogy of morals”. In this text, when dealing with his “perspective knowledge”, Nietzsche reveals to us, through the example of priestly corruption, how the affective and volitional content of a “will to truth” gave rise to that “ancient, dangerous conceptual fable that establishes a ' pure subject of knowledge, free from will, alien to pain and time'” (GM III 12). In his view, this obsessive search for truth guided by the Aufklärung has consolidated itself in our culture in such a way that intellectual probity now has to denounce all and any form of lying. She does so, without realizing, however, that the belief in the unconditional value of the truth is, in the genealogist's view, just another form of lie in which the spiritual core of modernity lies: the belief in the unconditioned.

From the genealogical perspective, it is not through an analysis of the truth of a discourse that a philosophy is probed, but rather by inquiring about its physiopsychological and affective motivations. Only in this way would it be possible to bring the view closer to those obscure motivations of philosophers, after all the origin of a philosophy is always revealed by the “symptoms of the body” (Prologue 2). It was following the trail of these symptoms that Nietzsche was able to identify how the vast majority of the history of philosophy was nothing other than a history of sick men; men who built their “majestic moral edifices” (Prologue 3) on the weakness of the affections of their decaying bodies. As mentioned in “Gaia Ciência”:

The unconscious disguise of physiological needs under the guise of objectivity, of the idea, of pure spirituality, goes so far as to frighten—and I have often wondered if, until now, philosophy, in general, has not been just an interpretation of the body and a bad - understanding of the body. Behind the supreme value judgments that have guided the history of thought, there are hidden misunderstandings of the physical constitution, whether of individuals, classes and entire races. We can see all the daring insanities of metaphysics, in particular its answers to the question of the value of existence, first of all as symptoms of certain bodies (…) (Prologue 2).

As Wotling has shown, through his hypothesis of the will to power, genealogy is not only able to “philologically decipher values, but it also founds a theory of the value of values, that is, of the value of interpretations” (2013). This "theory of the value of values" cannot be restricted to the old frontiers of knowledge based on the search for truth, its "clinical work" requires the use of new conceptual tools, more complex and fluid, in this case, those that, as an expression of the body, can be identified as promoters (health) or depressants (disease) of life itself:

“Now, the privilege accorded by Nietzsche to the physiological and medical metaphorical language does not reside only in the fact that it makes the interpretive activity of the will to power appear at the origin of every phenomenon of culture, but also resides in the fact that it makes it possible to reveal, behind a given culture, a certain state of the body […]” (WOTLING, 2013).

From this symptomatological evaluation of modernity, a new form of judgment and philosophical behavior can be seen, moving from truth to value status, that is, from truth to health. This is not to say, however, that the notion of truth has no meaning in the course of the genealogist's diagnosis, as it is as important as the statute of probity and intellectual honesty is for any investigator, what it is definitely not is the condition first of your investigation. What moves the genealogist is not a “will to truth”, but the condition that is characteristic of his ability to evaluate statutes of truth from the perspective of wills to power, that is, his ability to evaluate dispositions as affirming or depressing life. In this context, the task of the historian of morals is no longer just a diagnosis of the problems generated by the Socratic-Christian perspective and starts to appear as a true art of healing for an unhealthy experience. This is the new task of the genealogist and the “philosophical physician” (Prologue 2), not the truth, but being “someone who pursues the problem of the general health of a people, an epoch, a race, of humanity”. This new researcher must have the courage to pose the real problems that afflict human history and understand that the fundamental question of philosophy so far “has not been the 'truth' at all, but something different, such as health, future, power, growth. , life…” (Prologue 2). It is in this context that the philosopher can claim that his suspicion is a “new”, “foreign” language (BM 4), a new procedure that is capable of placing not the truth, the origins, or even the conservation of life as a goal. , but above all, its expansion. “Starting from a representation of life (which is not a desire to preserve itself, but a desire to grow) I have given an overview of the fundamental instincts of our political, intellectual and social movement in Europe” (FP 1885 2[179] ). As the philosopher states, the falsity of a perspective or discourse is not the object of the question, the problem is the goals, the objectives that are cultivated in a certain worldview:

The falsity of a judgment is not yet for us any objection against that judgment: it is in this, perhaps, that our new language sounds most foreign. The question is to what extent it is life-enhancing, life-conserving, species-conserving, perhaps even species-enhancing; and we are inclined in principle to affirm that the most false judgments (among which are the synthetic a priori judgments) are for us the most indispensable, that without letting logical fictions be valid, without measuring their effectiveness by the purely invented world of unconditioned, equal-to-himself, without a constant falsification of the world by number, man could not live - that to renounce false judgments would be a renunciation of living, a denial of life. To admit untruth as a condition of life: this undoubtedly means to put up resistance, in a dangerous way, to habitual feelings of worth; and a philosophy that dares to do so simply places itself beyond good and evil (BM 4).

This process of subversion of knowledge based on the idea of truth can be observed in the criticism made in “O twilight of the idols”, in this case, through the relationship between what Nietzsche identifies as a “sound moral” (Gesunde Moral) and a “unnatural morality” (Widernatürliche Moral):

“I formalize a principle. All naturalism in morals, that is, all sound morals, is dominated by an instinct for life, — every commandment of life is filled with a certain canon of "ought" or "ought not"; every hindrance and hostility is thereby set aside. . On the contrary, unnatural morality, that is to say, almost all morality that has hitherto been taught, venerated, and preached, is directly directed against the instincts of life, — it is a now secret, now noisy and brazen condemnation of those instincts” ( “Morality as anti-nature”).

Now, his new critical reference is precisely a hierarchy of health. It is the “instincts of life” and the inclination of each morality between an idealized, compassionate and castrating perspective [Castratismus] (“Morality as anti-nature”), which classifies the opposition between two distinct modes of valuing. On the one hand, the instinctive perspective linked to “health”, and on the other, the idealist reading, associated with “anti-nature”. This is the same idea that reappears in the section of “The Twilight of the Idols”, entitled “The Problem of Socrates”:

“The crudest light of day, rationality at all costs, the clear, cold, cautious, conscious life, without instinct, in resistance to instincts, was itself only a disease, another disease – and by no means a path of recovery. return to “virtue”, to “health”, to happiness… Having to fight instincts — this is the formula of decadence: while life ascends, happiness equals instinct” (“Socrates’ problem”).

In Versuch's idealist perspective, "life is not enough in itself, it is necessary to find its truth, and only then, for this, it will be worthwhile", this life - which on a large scale is still the modern perspective - is a life idealized, a form of anti-nature to life itself, because life is not taken as a measure and value, but an “idea” of life. In this unconfessed anti-nature, the “ideal” is worth more than life itself. This ideal, whether in the form of a weltanschauung, a religion, a truth, or even a morality, cannot escape what constitutes it: a will to power that wants to falsify its interpretation as a text, which wants to impose a vision as effectiveness. Thus, instincts are denied and sometimes even belittled, since the truth can only walk together with an “idea of life” and not with life itself. In the sense of this argument, we understand together with André Martins that genealogical research, “instead of seeking a truth of what has already been given, the reconstruction of facts, seeks to interpret affections genealogically present in the origin of ways of life and forms of culture” (MARTINS, 2004). In other words, it is an interpretation that, in spite of the truth, instrumentalizes the idea of health as a counter-concept of the truth, its most direct overcoming.

In short, health goes beyond the point of view of truth, and beyond: it allows the genealogist to take into his hands the process of hierarchy that permeates everything that exists in time. Criticism thus becomes an experience of continuous and profound reassessment of that “will to system” expressed through a doctrine in O Twilight of the Idols (“Sentences and Arrows”). From that perspective that figures as the basis of Western thought and which, to a large extent, is still based on the metaphysical “principle” that “God is truth, that truth is divine…” (GC 244). As Oswaldo Giacóia observed:

“With 'Beyond good and evil', a project of historical-critical reconstitution of the supreme values of western culture is instituted, whose objective is to carry out, in a dimension of absolute radicality, the “chemistry of concepts and feelings” that the inaugural aphorism of “Human, all too human” established as a necessary condition of all true historical philosophy; it is, therefore, to show, with abandonment of any and all optimistic belief in a progress of the spirit, tending to the realization of a realm of truth and freedom, as the most beautiful and sublime formations of the western culture (that is, the supreme references value of morality) plant their roots in the dark and shifting swamp of the ardent impulses of the “human animal”; it is about allowing access to the suffocating and bloody torture chambers where the supreme ideals are manufactured” (GIACÓIA-JÚNIOR, 2014).

“It is necessary to emphasize, however, that the act of employing notions such as health, expansion and strengthening as a criterion for a new way of interpreting the truth should not be understood here as an attempt to substitute one norm for another. By taking health as the object of his concerns, the genealogist does not exactly seek to establish a judgment of predilection on a particular interest or interpretation, quite the contrary: his objective is to evaluate inclinations, that is, the disposition or unwillingness to strengthen, aggrandizement, and increase in the potency of life, that is, everything that, as the philosopher pointed out, can be seen as naturally good and healthy: “the increase in the feeling of power” representation of “the happiness itself, what is good”” ( AC 3).

This is the “logic” of its subversion, the understanding that, if for intellectual probity we cannot stop drinking from the source of truth, on the other hand it is health and the impulse to life that must guide the genealogist. As Paul van Tongeren pointed out:

“The 'passion for knowledge' (FW 3 107 and 123), on the one hand, actually represents a moral quality, on the other hand, however, a threat to life itself: whoever passionately asks and seeks knowledge will fight every lie, and also those that are more pleasant and even more necessary to life. The thinker becomes a battleground where the impulse to life and the impulse to knowledge fight each other” (2010).

It was this subversion of comprehensibility that allowed the genealogist to see that, in the dynamic process of the “will to power”, there cannot be facts, but only interpretations. It is a way of thinking that, far from leading the genealogist to an aporia, leads him to an understanding of his condition as a “philosophical doctor” (Prologue 2), of his imperative need to diagnose having in mind not only the truth or the diagnosis of the problem, but its status for strengthening or weakening life. The genealogist, therefore, has the task of hierarchy, of properly diagnosing those forces that contribute to the expansion of life or to its depression, conservation, maintenance and diminution, etc. As summarized by Oswaldo Giacóia, Nietzsche's genealogical diagnosis can be described in this context as a therapeutic critique indispensable to the transvaluation of the values of which his late philosophy speaks:

“The history of culture becomes a succession of interpretations, reality presents itself as interpretation, symptomatology as an interpretation of interpretation or, paradoxically, as an interpretation to which no definitive text underlies. The genealogy of morals transforms the history of Western culture into a masquerade of the will to power. […] According to this perspective, the historical transformations that Western culture undergoes acquire the meaning of moments in the process of development of nihilism, whose intelligence and reflection lead to the urgency of a therapeutic critique, preparatory to the transvaluation of the values of decadence. Much of this therapy is constituted by the ultimate philosophy of Nietzsche” (GIACÓIA-JÚNIOR, 2014).

In the script of this therapy, it is possible to trace new routes and avoid the usual paths of rationality and the formalism of logical-academic knowledge, as is the case with most experiences of the body. This is the meaning of the new comprehensibility of which the philosopher speaks. Overcoming the demands of rationality, academicism, science: “We others, we immoralists […] open our hearts to all kinds of understanding” (CI Moral as anti-nature 6). Among the new forms of understanding is the knowledge through suffering, the search for the novelty of the experiment, of the “open sea” (GC 382), and even the spiritualization of exploration, because now, the doctor can, “thanks to his suffering, to know more than the most intelligent and wisest can know, to have been 'at home' and known in many distant and horrible worlds, of which 'you know nothing!'” (BM 270).

“'The Will to Cruelty': Nietzsche and His 'War Machine'”

For Reinhard Maurer, the warlike and combative rhetoric of Nietzsche's text must always be seen as a “compensatory thinking” (1995). With this, Maurer wants to point to the fact that the frequent exaggeration and aggressiveness of Nietzsche's rhetoric plays a role within his text. It works like the weight of a scale that seeks to compensate for the usual distortion of a one-sided perspective bequeathed by morality. In his writing, Nietzsche would need to balance that moral disproportion “through the emphasis on the repressed aristocratic counterpole” (MAURER, 1995). Thus, the irruptive tone of the Nietzschean text should not be taken literally, but only as another strategy of his “war machine”, a way of compensating for the overvaluation of certain moral attributes to the detriment of others.

Obviously, it is not possible to disagree with Maurer regarding the need for care in reading Nietzsche's text. True “ties and nets for unsuspecting birds” (HH Preface 1), his books demand a careful reading, or as Nietzsche himself points out, “a reader like me deserves it, who reads me as the good philologists of yore read their Horace ” (EH Why I Write Such Good Books 5). However, if, on the one hand, there is a real need to be careful when reading Nietzschean metaphors and concepts — such as will to power, cruelty, Jewry, slavery; on the other hand — it is also true that in order to be “the bad conscience of its time” it is essential to exercise a certain distance from that discourse that intends to establish a certain set of virtues as untouchable, as is the case of the Western-Christian perspective of: truth, equality, justice, and compassion. Thus, if it is essential to know how to separate the performative hyperbole from Nietzsche's text, it is also essential to understand that moral distancing figures as one of the central strategies of the Nietzschean healing art, and that, sometimes, the confessed immoralism of his writings is not a linguistic instrument, but the experimentation of a new perspective. That is, of a new reading that, because it is too human — read immoral — is affected by all sorts of softenings, distortions and re-readings interposed by its interpreters who are more attached to the values that translate them as modern men.

As Onfray pointed out, taking into account the danger that consists in a caricatured signature of Nietzsche's text, the best way to serve the author of Zarathustra would be "by refusing the usual boutades of superficial commentators", distancing himself as much as possible from the temptation of impregnate the philosopher's text with the heterodoxies and vices that we carry. After all, historiography confirms that: “Under his writing, there is everything and the opposite of everything, that there are quotes in the complete work that can justify both a position and its denial [...] to the skillful seamstresses and the forgers — I think of a Jesuit by habit… — to turn Nietzsche more or less into a Christian or any graceful nonsense!” (ONFRAY, 1999).

This concern is not unjustified, since since the first deformations of his sister, Nietzsche has already been transfigured into an anti-Semite, a defender of “animalistic” brutality and irrationalism (HEIDEGGER, 2007), he was associated with fascism, read as a “social philosopher of capitalism” (HEIDEGGER, 1891). ” (MEHRING, 1992), an advocate of a kind of “Nietzschean socialism” (ANCHHEIM, 2008), “liberal constitutionalism” (EGYED, 1998), and there were even authors who see in Nietzsche’s text a kind of “liberal Christianity” (EGYED, 2006). non-religious” (ROLLAND, 1995), that is, “benevolent” (REGINSTER, XNUMX). These deformities paint, as Maurer pointed out, a “soft-Nietzsche” in which his philosophy becomes “almost synonymous with love and justice” (MAURER, XNUMX).

Onfray himself, despite his criticism, also presents some attempts to morally reform Nietzsche's text. For if, on the one hand, he claims not to politicize his investigation, on the other, he seeks to forge a reading of the Nietzschean text that supports his own political-philosophical predilections, in this case, manufacturing a feminist and hedonistic dimension in Nietzschean philosophy:

“My Nietzsche is fragile, he loves women, but he doesn't know how to say that to them, so first he protects himself, then he exposes himself to misogyny; he practices sweetness, politeness, discretion in his life — '[…] If he is not a hedonist' — I am, of course, familiar with the texts in which he associates this philosophical option with decadence and nihilism — at least he takes up on his own the tradition of his dear Greeks, all of whom were eudaimonists: none, in fact, avoids the question of the sovereign good. Neither does Nietzsche. How to live to be… shall we say, happy? Or rather: as less unhappy as possible — another way of defining hedonism…” (ONFRAY, Preface, 4).

Despite this surreptitious vice of imposing interests on Nietzsche's text, what these authors fail to perceive is that this process of acidity of Nietzsche's criticism seems to be indispensable if we have in mind the history of power relations and the rigging of the horizon of possibilities of western man. It is not without reason that Nietzsche calls his philosophy “symptomatology” (CI The “improvers” of humanity) when he asks himself about the goals and meaning of a certain interpretation of life. His diagnosis, thus, points not only to the history of the problem, but seeks to present ways of breaking with its domination. Not recovering this morality, but giving it a “pin for it to burst” (AC 7). This is, as Paschoal indicated when speaking of Stegmaier:

“[The] reason why he would need to destabilize the old beliefs and make possible the emergence of other possibilities, to give a new orientation in the field of morals. In this sense, for Stegmaier, in a thesis that we have followed to a large extent, “criticism is […] only a means and presupposition for [his] philosophy, including his Genealogy of morals” (p. 3), in the same way as the The history of the emergence of morals, carried out by Nietzsche, is only a means to “de-legitimize” (p. 55) the dominant morality. This gives support to our hypothesis of genealogy as an action and of the genealogist as a participant in the field described by him” (2014).

This is the question of the “room for manoeuvre” [Spielräume] that became famous in Stegmaier's text, namely, “a concept or image for regulating the validity of rules. […] a space in which someone or something can behave according to its own rules of action […]” (STEGMAIER, 2013). Morality itself, as an expression of a will to power, is the agent of this delimitation, it is what imposes limits on affections, thoughts, and life itself. However, even after starting the process of “great liberation” (HH Prologue 3) from these limits, and with the possibility of expanding perspectives, this new “delegitimizing”, as we have seen, presents a problem: the modern sensibility. And this is, in our view, a point that has to be questioned.

One of the most exemplary cases of this dilemma between immoralism and modern sensibility is found in aphorism 259 in the book “Beyond good and evil”. In this text, Nietzsche seems to answer a question that he himself raised a few years earlier in a note from the autumn of 1885, namely, the “problem: [from] how deep into the essence of things does the will towards goodness descend? The opposite of this is seen everywhere, in plants and animals: indifference or harshness or cruelty. […]” (FP 1885 4). This brief note, in the context of BM's aphorism 259, can be understood as a centerpiece of his moral displacement, his immoralism. This is a true example of modern man's inability to deal with what, from the point of view of Christian sensibility, is understood as negative, ugly, immoral. That is, the opposite of everything that can be understood as “the primordial fact of history” [das Ur-Faktum aller Geschichte], that aesthetically unpleasant history of power relations in time. As the German philosopher says:

“Abstaining from offense, violence, mutual exploitation, equating one's will with that of the other: in a crude sense this can become a good custom between individuals, when conditions exist for it (namely, their effective similarity in amounts of force). and measures of value, and the fact that they belong to a body). But as soon as one wanted to carry this principle forward, possibly taking it as the basic principle of society, it would readily reveal itself for what it is: the will to negate life, the principle of dissolution and decay. Here we must think radically to the core, and guard against any sentimental weakness: life itself is essentially appropriation, offense, subjection to what is strange and weaker, oppression, harshness, imposition of one's own forms, incorporation and, at the very least, more restrained, exploitation — but why always use these words, which have long been marked by a defamatory intention? This body, too, in which, as we assumed above, individuals treat each other as equals—this happens in every sane aristocracy—must, if it be a living and not a dying body, do to other bodies all that their individuals refrain from doing. one another: it will have to be the will to power incarnate, it will want to grow, expand, attract to itself, gain dominance — not because of any morality or immorality, but because it lives, and life is precisely the will to power. At no other point, however, does the general conscience of Europeans resist the teaching more; Everywhere nowadays, even under scientific guise, people dream about future states of society in which the “exploratory character” will have to disappear — to my ears this sounds as if someone promised to invent a life that abstained from all organic function. “Exploitation” is not typical of a corrupted, or imperfect and primitive society: it is part of the essence of what lives, as a basic organic function, it is a consequence of the will to power itself, which is precisely the will to life. Assuming this is a novelty as a theory—as a reality is the overriding fact of the whole story: be honest with yourself up to this point!” (BM 259).

It would be interesting to begin a comment on this aphorism by noting the apparent contradiction between the aforementioned “primary fact of all history” (BM 259) and the idea “that there are absolutely no moral facts” (CI Os “Improvers” of Humanity). After all, how is it possible to speak of a “primordial fact” if one of the central ideas of his genealogy is the notion that everything that is human and, without exception, suffers the action of time? Despite the apparent contradiction, this dialogue is possible precisely because, as the philosopher indicates, he speaks of “a primordial fact of all history”, that is, there is no universality in man, but only historically persistent elements. Indeed, this is what often confuses philosophers and social scientists about the human; reckless, call “human nature” what is historical, whether in the form of physiology or culture. Permanent, therefore, is only historical “nature”, and this is, from the perspective of the will to power, “exploitation”” (BM 259).

It is thus, without many metaphors and with a clear and direct language, that the philosopher warns us: “here we must think radically”, “to the bottom, and guard against all sentimental weakness: life itself is essentially […] and , at least and more restrained, exploitation” (BM 259). This kind of claim, that “at no other point […] does the general consciousness of Europeans resist teaching more” (BM 259), is not just a hypothesis that relates to a general idea of exploitation, but is life itself in its own right. its most basic structures and in the most diverse fields that, from the perspective of the will to power, acts as: “appropriation, offense, subjection of what is strange and weaker, oppression, harshness, imposition […]” (BM 259). And this is a problem for modern man. For it suffocates and crushes the civilized spirit of this modern type, the realization that perhaps it may be true to say that everything that “deep down this world has never entirely lost a certain odor of blood and torture […]”, and that “to see suffering is good, and making suffer even more good” (GM II 6). For the meek and civilized type of modernity, cruelty does not represent something human, all too human, but the horror and villainy of immorality.

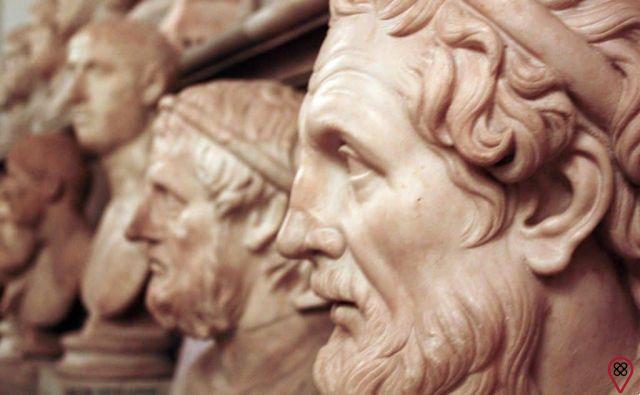

The Greeks and the peoples of antiquity, as an opposite example of this spectacle of horror, had already understood that this natural and paradoxical “cruelty” (FP 1885 43) is not only human, but divine. Thus, they made of their gods everything that was all too human in history, for “[…] not even the Greeks knew of a more pleasant condiment to add to the happiness of the gods than the joys of cruelty.” (GM II 8).

For the “sheep” of modernity, however, the morality of the “birds of prey” is absurd madness, and celebrating the “joys of cruelty”, a true nonsense within the morality that has peace as its supreme good. This reasoning, however, so common to modern morals and virtues, is built on hypocrisy and forgetfulness. For only those who conveniently forget are able to deny that even in the most violent act, even in the greatest of moral horrors - murder - there can be virtue. What, for example, would a Lacedaemonian born who, as a rule, define the passage to adulthood — in the Cryptean ritual — say, through the “hunt” and murder of a Hilota slave? Wouldn't that be a Spartan virtue? A design of your ability and nobility? Or just cruelty? The issue here, therefore, is not just pointing out the falsity of the creation of “values in themselves”, but above all, highlighting the castration of negative affects by morality and the dangerous practice of creating idealized fictions of man and life. As the philosopher said:

“Soft, benevolent, indulgent, compassionate feelings — after all of such high value that they became almost “values in themselves” — for a long time had precisely self-contempt against them: one was ashamed of mildness, as one is ashamed today. of hardness” (GM III 9).

You may also like

- Discover what the philosophy of participatory impartiality is

- The importance of ethics and morals in your life

- Discover the importance and origin of Peripatetic philosophy

- Friedrich Nietzsche — Who was this great philosopher and how did he collaborate with the world?

- Understanding Freud in religion, according to philosopher Nilo Pessanha

- Your moral center and heart values

The problem, as it turns out, is that modern man, that humanistic and compassionate type of moral animal, understands that “exploitation” is suffering, and that all suffering must be avoided. This modern type, hedonistic by nature, is incapable of seeing suffering as a form of useful knowledge, as something natural, and thus, continues to crave those old ideals that seek to end the “exploratory character” (BM 259) of man: “refrain from offense, violence, mutual exploitation, equate one's will with the other's” (BM 259). Thus, they choose their ideals of an improved future for humanity: a classless society, the end of inequality, social justice, the Welfare State, and many other utopias for the betterment and betterment of man who seek peace instead of tension.

It is necessary to clarify, however, that we do not advocate here a defense of cruelty and unruly exploitation, nor any form of return to models and morals of the past. Cruelty and exploitation are facts, they need no defense. The problem that we seek to point out with this discussion is the total incapacity of Western morality to, in good conscience, incorporate morally negative elements and progressively act towards the “spiritualization” and “divinization” of cruelty”, “the sacralization of the most powerful, most terrible and more famous, said with the old image: the deification of the devil” (FP 1885 1).

This exercise, far from being a simple praise of an excessive aggressiveness, compels the spiritualization of the passions, their incorporation: “no longer having in the foreground the opposition between the maligned impulses” (FP 1885 1), which, on the contrary, to drive castration, has its use focused on the discovery of strategies to potentiate the tension of these explosive energies in constructive and enriching ways for life. As he made clear in “Twilight of the Idols”:

“All passions have a period when they are merely fatal, when they carry their victims down with the weight of stupidity—and a later, much later period, when they marry the spirit, become 'spiritual'. Before, because of stupidity in passion, there was war on passion itself: there was a conspiracy to annihilate it — all the old moral monsters are unanimous in this: “il faut tuer les passions” [the passions must be killed]” ( CI “Morality as anti-nature”).

Spiritualizing the passions, therefore, presupposes neither a return to the brutality of the past, nor the extermination of these affections, but their transfigured experience. As he made clear in an 1888 note, his task is:

“Dominion over the passions and not their weakening or extirpation! The greater the power of control of our will, the more freedom can be given to the passions. The great man is great through the leeway [Spielraum] of freedom of his appetites, but he is strong enough to tame these wild appetites” (FP 1888 16).

This is the difference in the spiritualization of Rome against Judea; of experimentation with the extremes of the body and its mortification in priestly aesthetics; of Caesar's morals against São Paulo; or the creation of a God who is a mirror of the power of life in opposition to the “god” who is a reflection of universal misery. Like the type of great health in Nietzschean therapy, he is the one who is able to experiment with these tensions and bring to fruition in himself - with a good conscience - these negative affects, the type of man who must be cultivated as a promise of the future and of life. greatness. Here, evidently, there is no recipe or manual of conduct that prescribes how this spiritualization of morally negative affects should work. But if we can intuit that the idea of spiritualizing implies a refinement, a change in its function and form, we must also be careful not to assume here a suppression or even a total disfigurement of affect as is done by the little priestly therapy. For the “good use” and spiritualization of these affections occurs, above all, through years of experiment and attempts, with attention to the peculiarity of each case, but still, of their use:

“We believe that harshness, violence, slavery, danger in the streets and in the heart, concealment, stoicism, the art of temptation and diabolism of every kind, everything that is evil, terrible, tyrannical, everything that is beast of prey and serpent in man serves the elevation of the species “man” as well as its opposite—but we have not yet said enough, in saying only this, and in any case we find ourselves, with our speech and our silence at this point, at the other end of all modern herd ideology and aspiration: as its antipodes, perhaps?” (BM 44).

In this context, we could say that, paradoxically, the surpassing of the human in a future “beyond man” begins with the recognition of everything that is too human in its Naturgeschichte, starting precisely, in this case, with the morally negative affects, such as the cruelty case.

“Seeing-suffering is good, making-suffering even better—this is a harsh phrase, but an old and solid axiom, human, all-too-human, to which perhaps even the apes subscribed: it is said that in the invention of bizarre cruelties they already announce and how they “prelude” man. Without cruelty, there is no celebration: this is what the oldest and longest history of man teaches — and in punishment there is also a lot of festive! (GM II 6).

A recovery of the neurosis that shapes modern morality necessarily involves the acceptance of cruelty, its spiritualization and, why not, the example - but not imitation - of the Romans in their integration of cruelty to the most supreme values, to life itself and to everything which may be called great in man. The philosopher and genealogist in this context, should “be almost inhumane” (HH 1) in moral (Christian) matters, only then, as a moralist (investigator of morals), could he point out the differences and hierarchies between moral perspectives, especially those that, for account of their immorality present themselves as “too human”.

“The desire for voluptuousness”: sensuality against moral modesty”

Inaugurated by Nietzsche, the theme of the sublimation of sexual stimulation is, alongside the history of the moral-civilizing process, the cradle of all modern psychology with a Freudian background. Despite the famous denial professed in the Interpretation of Dreams, the reality is that it is impossible not to identify similarities between the Basel philosopher and the Vienna psychologist (cf. GASSER, 1997). After all, even though both authors have different methodologies and sometimes even different theses, they agree on many points, such as the identification of renunciation of the satisfaction of drives in the psychological construction of the human; in the hypothesis that this affective castration is a central theme in the formation of modern malaise; and in the argument about the possibility of a sublimation of the passions, in the form of a spiritualization or ennoblement of the affections. As Almeida highlighted: “Nietzsche, like Freud later, frequently resorts to images that evoke the diversion of sexual energy to the domain of artistic, religious, cultural creation […]” (ALMEIDA, 2008). This redirection of sexual energies seems to be the core of the problem that is addressed by Nietzsche when referring to “sensuality”, in this case, dealing with the positive meaning of this spiritualization in music, art, and in “love” (CI Moral as anti-nature). ), but above all, as a criticism of its negative and castrating form represented by the ascetic ideal and the suffering generated by this perspective.

As demonstrated in the third dissertation of “To the genealogy of morals”, the ascetic ideal contaminates all spheres of life and human representations with the “hospice and hospital air” (GM III 14) that emanates from its unhealthy nature. We find ramifications of this nefarious ideal, for example, in theology (GM III 1), philosophy (GM III 6), art (GM III 5), science (GM III 14), nationalism (GM III 26), historiography (GM III 26), and wherever “hatred of the “world” prevails, the curse of the affections, the fear of beauty and sensuality, [in short] a side-of-there invented to better defame the side-of-there. -here” [VCS] (NT Preface 5). Unlike the lustful habits of the Greeks and Romans, Christian Weltanschauung understands sensuality as something to be despised, reproved, suppressed, diverted from its vital source and transfigured into "original sin." “This species [of life] hostile to life” [VCS] (GM III 11) has as its objective the production of a sick type of human, pruned in its nature, castrated of its humanity, in the name of chastity, and of an ideal of man and purity, everything that is vigorous and life-promoting is subverted. This castrating ideal understands as something negative everything that, in aristocratic values, was considered to be of the highest value, among these, virility and sensuality. As the philosopher summarized in the book that opens the “curse on Christianity”:

“The Church fights passion with extirpation in every sense: its practice, its “cure” is castrationism. She never asks: “How to spiritualize, beautify, divinize a desire?” — at all times, in disciplining, she placed the emphasis on eradication (of sensuality, of pride, of greed for domination, of greed, of the craving for revenge). — But attacking the passions at the root means attacking life at the root: the practice of the Church is hostile to life…” (CI “Morality as anti-nature”).

It was in this swampy riverbed dug by the priest, poisoned by guilt and resentment, that “[…] the hostility to life, the spiteful, vindictive aversion to life itself” (NT Preface 5) was cultivated. A specifically Christian characteristic, — but not restricted to it — the ascetic ideal values the idea of permanence of being to the fluidity of becoming; he invents a reality as opposed to the apparent; precedes reason over the body; and the soul on the materiality of life. Its supreme ideal of value is the perpetuation of a life that degenerates, the negation of every vigorous impulse, therefore, its values rely on the negation of life, of itself, and of everything that, everywhere once was something. once understood as health and strength:

“Christianity was, from the beginning, essentially and basically, disgust and disgust for life in life, which only disguised itself, only concealed itself, only adorned itself under the belief in “another” or “better” life. Hatred of the “world”, the curse of affections, fear of beauty and sensuality, a side-there invented to better defame the side-here, deep down a longing for nothingness, for the end, for repose, to arrive at the “Sabbath of Sabbats”” (NT Preface 5).

Passed on to the philosopher by the “precarious conditions in which philosophy emerged and subsisted” (GM III 10), the ascetic ideal was identified in the first aphorisms of the third dissertation of Genealogy as something that contaminated both the art of Richard Wagner and the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. Interestingly, Nietzsche begins this dissertation with a kind of praise for Wagner, pointing out how in the past the author of The Nibelungs Ring was an artist who pursued “the highest spiritualization and sensualization of his art […]” (GM III 3), when, at the time, he was still walking in the footsteps of Feuerbach and his “healthy sensuality” (GM III 3), “had he finally unlearned that? At least it seems that in the end he had the will to teach it… (GM III 3). Seduced in old age by the ascetic ideal, “Wagner turned into its opposite” (GM III 2), as a kind of “identification and inclination to medieval soul conflicts” (GM III 4) began to inhabit in him, an “obscurantist” tendency ( GM III 3) to “pay homage to chastity” (GM III 2) and undertake “a hostile departure from all elevation, discipline and severity of spirit” (GM III 4). We soon discovered that the origin of this change of direction of the Wagnerian ship was the reef of Schopenhauer's philosophy that ran aground there once and for all the Flying Dutchman. After all, “who could even imagine that he would have the courage for an ascetic ideal, without the support that Schopenhauer's philosophy offered him, without the Schopenhauer authority, prevalent in Europe in the 70s?” (GM III 5).

As described in the sixth aphorism of this dissertation, Schopenhauer took upon himself the “Kantian conception of the aesthetic problem” (GM III 6) as a strategy of recovery and refuge from his tortured existence, against life and “against sexual interest” (GM III 6). By incorporating into his philosophy a notion of peace and “aesthetic contemplation” (GM III 6) against the “torture” (GM III 6) of denied sensuality, Schopenhauer found a way to produce what he described as “an effect of the beautiful, the calming effect of the will” (GM III 6):

“Let us listen, for example, to one of the most explicit passages, among the many he wrote in praise of the aesthetic state (The World as Will and Representation, III, section 38), let us listen to the tone, the suffering, the happiness, the gratitude with which these words were spoken: “This is the painless state which Epicurus praised as the supreme good and state of the gods; for a moment we withdraw ourselves from the hateful pressure of the will, we celebrate the sabbath of the servitude of the will, the wheel of Ixion stops...” (GM III 6).

The avowed falsification of the “désintéressement” of the Kantian aesthetic of the beautiful is evident in Schopenhauer’s philosophy, there speaks a “tortured” spirit (GM III 6), there speaks the denial of a sensuality that despises itself and from this contempt makes its philosophy . Schopenhauer “really treated sexuality as a personal enemy (including his instrument, the woman, this instrumentum diaboli [the devil's instrument]) […] (GM III 7). Incorporating the denial of the ascetic ideal, Schopenhauer chooses castration as a philosophical practice and experiences the neurosis resulting from the denial of the will as eternal suffering. His conclusion that life is suffering should not sound strange to one who understands the question:

“'What does it mean for a philosopher to pay homage to the ascetic ideal?', here is at least a first indication: he wants to free himself from torture” (GM III 6).

The maximum negation is completed when this tortured perspective is led to philosophize, for its conclusion, based on the principle that life is suffering, is that: “the best of all is for you entirely unattainable: not having been born, not being, nothing to be. After that, however, the best thing for you is to die soon” (NT 3).

Anyway, as a philosopher and researcher, I, Nilo Deyson Monteiro Pessanha, purposely wanted to bring this type of content and reflection to free the reader's conscience from some kind of impediment in the sense of understanding a text and interpreting an author through philosophical reflection. For those who wish to delve deeper into this research, I have put some references for you to study. Finally, gratitude to the Great Architect of the Universe for the opportunity to register another article for eternity in the intellectual world while the modernity of archiving writings through the means of technology lasts.