Today's text is about “The idea of sin and its consequences for posterity in the myths of Tantalus and Adam and Eve”.

Dear reader, I have prepared here a survey with references for you to have a variety of options to investigate, search in sources of great relevance on the subject.

The question of human suffering has always been, in the history of humanity — and one could also say that in the history of religions — a nuisance. Dealing with limits is not easy for those who always try to overcome them. It is in the face of questions about the limits of the human condition that the human being arrives at the myth, and from the myth he leaves for a more elaborate and systematized reflection.

The present study wants, in this sense, to make an approximation between Greek mythology and theological reflection on the human condition. To this end, this article is divided into two sections:

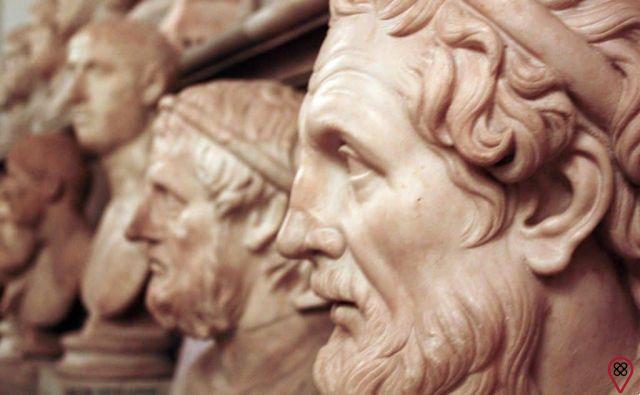

1st: The myth of Tantalus and the curse on his offspring, where, according to Greek mythical literature, you will find the reasons for the misfortunes that accompany the descent of a first man-god who commits a fault.

2nd: The theme of the consequences of the sin of Adam and Eve in Christian theology, starting from the Pauline reading of Adam's sin or hamartia and its effects for all humanity.

It is not the intention to confuse the myths, as if one could have been the basis for the other, but to find points of convergence between the two regarding the issue of the human condition.

“Greek mythology, as we know, seeks to make sense of the great dramas of humanity. Thus, it is not difficult to find themes in the myths concerning the condition of man in this world. Among the main themes worked in the myths are suffering, death, the misfortunes that befall humanity daily. In this way, it can be said that the myth seeks to illuminate reality and give it meaning, because, when considering the origins, it explains, for example, the current miserable condition of the human being” (RICOEUR, 1988).

In the myth of Prometheus, for example, one can perceive the “graceful” condition of everyone at the beginning. Because of his “cunning”, this situation is revoked. The act of a single person, in this sense, causes harm to all humanity at all times. However, in the case of the Prometheus myth, humanity inherits only the consequences of a wrong act, such as suffering and death. There is no inheritance of guilt, but of the consequences of Prometheus' act.

The myth brings four main characters: Zeus, Prometheus, Epimetheus and Pandora. Hesiod, the Greek poet who wrote “Theogony” and “Works and Days”, says that Zeus, the all-powerful god of the Greeks, had hidden fire from human beings, so that they would not live in idleness, making in a day what they should do in a year (HESÍODO, 2008). Prometheus, a Titan, son of Iapetus and Clymene, and brother of Epimetheus, in an act of betrayal, steals fire from the gods to give to mortal men. Enraged, he punishes not only Prometheus, but human beings as well:

“Son of Iapetus, skilful above all of them in their plots, it delights you to steal fire by defrauding my bowels; great plague for you and for men to come! To those, instead of fire, I will give an evil and all will rejoice in their hearts, spoiling this evil very much” (HESIOD, 2008).

Zeus says that Prometheus is "skillful in his plots", indicating the meaning of the name "Prometheus", which, as a masculine noun, means "cunning", "foreseeing", "prudent", "what he knows before". The result of Prometheus' cunning will be evil, which will come in the form of a beautiful virgin, Pandora, created from the mixture of earth and water and adorned by all the gods to be given as a gift from all the gods to Epimetheus, brother of Prometheus. Hesiod, in Theogony, states that Epimetheus is “without a hitch” and “from the beginning, it was an evil for men to eat bread” (HESIOD, 2009). This is because, upon receiving from the gods Pandora, Epimetheus soon falls in love with the virgin. Prometheus had warned Epimetheus never to receive a gift from the gods, but he did not think about what had been said by his brother, accepting the one who, lifting the lid of her jar, distributed to human beings all the evils that were given to him by the gods, leaving only in the jar the “Expectation” or “Hope”. Pandora becomes the symbol of doom (HESIOD, 2008).

“In the myth of Tantalus something similar happens. He too wants to be cunning with the gods. Wanting to put the omniscience of the Olympians to the test, he ends up unleashing a series of misfortunes not only for himself, but for all his descendants. Although being the son of Zeus and Pluto, the king of Lydia had already committed some crimes against the gods, such as: revealing divine secrets to men; steal nectar and ambrosia, food from the gods that gave them immortality; and, the most serious of all hamartiai, to offer his own son, Pelops, at a banquet to test the omniscience of the gods” (BRANDÃO, 2013).

Several classical authors, such as Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Virgil, Seneca, Hyginus, Ovid, etc., explored this myth and made known the misfortune that befell the Tantalids (descendants of Tantalus). The famous Trojan War, for example, is found in this unfortunate plot that is the story of the descendants of Tantalus, as will be seen later.

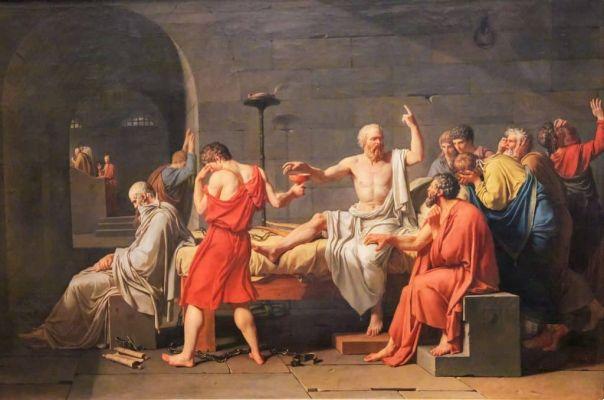

The Latin writer Seneca, in his work Thyestes, presents Tantalus as a curse, when in the first act he says:

“Do not let the heavens be immune from your wickedness: why do the stars shine in the firmament?... Let a deep night come, let the day disappear from the sky. He overturns these Penates, causing them hatred, killings, funerals and fills the entire house with Tantalus” (SÊNECA, 2008).

Filling the environment with Tantalus means filling the spirit of Tantalus, meaning the curse present in his offspring, recalling the misfortune thrown by the gods, as we will see below.

The Inheritance of the Curse of Tantalus:

As already stated, among Tantalus' crimes, the main and most tragic is that of serving his own son at a banquet to test the omniscience of the gods.

Tantalus was king of Lydia, married Dione and had two sons: Niobe and Pelops. One day, Tantalus invites the gods to a feast and, to test the metys, "cunning", "wisdom" of the gods, sacrifices his son, quartering him and serving him as food. Realizing that Pelops was not present at the banquet, the Olympians stopped and did not taste the delicacy served by the king. Meanwhile, Demeter, goddess of agriculture, worried about the kidnapping of Persephone and inattentive because of hunger, will devour a shoulder of Pelops. When they realized that the food in front of her was the son of Tantalus, the gods recomposed him and made him live again (BRANDÃO, 2013). In place of the shoulder of flesh devoured by Demeter, Pelops receives an ivory shoulder, as stated by Ovid (2014):

When born, this shoulder had been the same color as the right and flesh. Later, the body was dismembered, it is said, by the father's hands, and the gods put it back together. They found all but one of the pieces between the throat and the top of the arm. In place of the part that was never found, a piece of ivory was placed. And this done, Pelops was complete.

Horror grips the gods, and they throw Tantalus into Tartarus, condemning him to an eternal torment of thirst and hunger. He will be up to his neck in clear water; above his head are trees full of fruit. Whenever you feel thirsty, the water that is so close to your mouth will drain away, and when you feel hungry and want to pick some fruit from the trees above your head, the branches of the trees will move out of your reach. This is the so-called “torment of Tantalus”, as Ovid says: “You, Tantalus, catch no water, and the fruits that hang over you flee” (2014).

The scholar of Greek mythology, Junito de Souza Brandão (2013) states that:

“The mythical theme of Tantalus, in the inner struggle against vain exaltation, symbolizes rising and falling. His torment runs parallel to his hamartía: the object of his desire, water, fruits, freedom, everything is before his eyes and infinitely distant from possession. Deep down, Tantalus is the symbol of incessant and uncontained desire, always insatiable, because it is in the nature of the human being to live always dissatisfied. The further one advances towards the desired object, the more it eludes and the search begins again...

The first to experience the consequences of this hamartia is Tantalus himself. However, his attitude will bring disgrace to all his offspring. His daughter Niobe will see her fourteen children, seven males and seven females, die because of their pride before the goddess Latona, or Leto, who had only two children. Faced with this affront, Apollo will kill Niobe's seven male sons with arrows, while they hunt, and Diana, also with her arrows, will take the lives of the seven daughters (HIGINO, 2009). Here we already have a first situation of disgrace in the family of Tantalus after the punishment of the king of Lydia himself. It is said that Niobe, “desperate with pain and in tears, took refuge on Mount Sipilus, the kingdom of her father, where the gods turned her into a rock, which, however, continues to shed tears” (OVÍDIO, 2014; BRANDÃO, 2013; BRANDÃO). , XNUMX).

“Pelops, the one served at the feast, will also fall victim to the Tantalid curse, just as he will be cursed again because of a betrayal on his part. Pelops aspired to marry Hippodamia, who was the daughter of Oenomaus, king of Pisa, in Elis. But to achieve his wish, Pelops must accept the challenge to beat the king in a chariot race. The king owned the best horses in the region and, therefore, won all the suitors of his daughter. He had already defeated twelve suitors when Pelops presented himself. In order to defeat Oenomaus, Pelops will enlist the help of the royal charioteer, Myrtilus, who has agreed to sabotage the king's chariot. At the first start of the horses, the axle of the chariot broke and Oenomaus was thrown to the ground, being torn to pieces. Pelops thus succeeds in marrying Hippodamia, but in order not to leave witnesses to his crime, he will cast Myrtilus overboard. However, before dying, the coachman will curse Pelops. Thus, to the curse of Tantalus, there is added the curse of Pelops, the result of his betrayal” (BRANDÃO, 2013).

From the union of Pelops and Hippodamia, Atreus, Thyestes and Chrysippus, among others, were born. Chrysippus was murdered by his brothers Atreus and Thyestes, and they fled to Mycenae, carrying another crime with them (HIGINO, 2009). With the death of Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, who had left this life without descendants, the Mycenaeans hand over the throne to the two brothers, giving credit to an oracle. Then begins a bloody dispute between them that, once again, will mark the descendants of Tantalus.

It is said that, aiming for the throne of Mycenae, Atreus, after having found a golden fleece ram, had promised to sacrifice it to Artemis, goddess of the hunt, but instead he kept it and the golden fleece. , collect in a safe. His wife Aerope, in an act of betrayal, steals the golden fleece and gives it to Thyestes, who proposes a challenge to Atreus to see who would ascend the throne of Mycenae. This challenge was to show the people a golden fleece. As he did not know of his wife's betrayal, Atreus accepts the challenge. However, guided by Zeus, Atreus makes a counter-proposal: the king should be appointed not by the presentation of a golden fleece, but by an extraordinary act, a prodigy: if the sun followed its normal course, the throne would be occupied by Thyestes, if should the sun happen to return to the east, Atreus would be king. After accepting the challenge, all the people began to observe the sky. The sun, instead of following its course, turned to the east, and Atreus then assumed the throne (BRANDÃO, 2013).

“Later, Atreus would learn of his wife's betrayal of his brother, causing Thyestes to abandon Mycenae. This situation would bring as a consequence such a monstrous revenge that Seneca, through one of the characters in the work Thyestes, states that even Tantalus and Pelops would be ashamed of what would happen” (SÊNECA, 2008).

Pretending to be reconciled with his brother, Atreus will invite Thyestes to return to Mycenae, promising him land and inviting him to a feast in honor of the gods: “It is a great joy to see a brother. Give me that hug I've been waiting for. All wraths felt, be things past. From now on, we have to honor blood and family ties” (SÊNECA, 2008). However, those sacrificed will not be animals, but Thyestes' own children: Tantalus, who bears the same name as his great-grandfather, and who would be the first to die, and Plisthenes.

Seneca shows that everything is very well planned by Atreus: first, he offers land to Thyestes, who, at first, is suspicious, but later, given the way he is received, ends up believing in his brother's good intentions; he tells his brother that he would offer a sacrifice to the gods and invites him to a feast to seal peace between the two; he takes the sons of Thyestes prisoner, without his knowing it; prepare the altar of sacrifice; ties the boys' hands with purple ribbons used for sacrifices; blindfold them; prepares the incense, observing all the protocols for the sacrifice:

“The priest is himself, between ominous curses, with a cruel voice, he sings the funeral song. He stands in front of the altar, prepares the victims appointed to die. He prepares everything, without forgetting any part of the sacrifice... This act moved everyone... Only Atreus remains insensitive in his action, terrifying the gods, who threaten him and, without further delay, he places himself at the altar... that there is no respect for the family, was consecrated to his grandfather: Tantalus is the first victim… Then this one [Atreus] cruelly leads Plisthenes to the altar and unites him with his brother” (SENECA, 2008).

The story goes on, showing the cruelty with which Atreus cuts the victims' bodies apart, separating their limbs, ripping out their viscera, leaving only their faces and hands intact, to serve as evidence (SÊNECA, 2008).

When everything is ready, Atreus calls his brother to the feast, prepared with the flesh of his children. Feeling flattered by his brother's attitude, Thyestes asks that his children can participate in his happiness, hearing from his brother: “Believe! Your children are here, on their father's lap... you devoured your children in this cruel banquet” (SÊNECA, 2008). Terrified, Thyestes invokes the intercession of the gods, saying: “the gods will avenge me; my desire is that you be in their hands, so that they punish you” (SÊNECA, 2008). Faced with his brother's pain, Atreus feels vindicated.

The curse of Tantalus' descendants is not yet over. Thyestes will have his revenge through his son Aegisthus, the fruit of his relationship with his own daughter, Pelopia, who, some time later, fled to Mycenae and married her own uncle, Atreus.

When Aegisthus was born, he had been abandoned by Pelopia. Some shepherds found him and put him to suckle on a goat. Upon learning of this, Atreus sends for Aegisthus and raises him as if he were his son (HIGINO, 2009). Once grown, the king of Mycenae orders Aegisthus to kill Thyestes. Ignoring that this is his real father, Aegisthus follows Atreus' orders. In time, however, he discovers who his real father was, returns to Mycenae and kills his adoptive father (BRANDÃO, 2013).

Agamemnon and Menelaus: The Sons of Atreus and the Trojan War:

Atreus having been slain by Aegisthus, his foster-son, but the legitimate son of Thyestes by Pelopia, the son of Atreus by Aerope ascends to the throne of Mycenae: Agamemnon. He was known in antiquity for wanting to control the surrounding states, becoming the king par excellence of Argos, Mycenae and Lacedaemon. Agamemnon was married to Clytemnestra, daughter of Tyndareus and Leda, king and queen of Sparta, sister of Helen on her mother's side, as she was the daughter of Zeus with Leda.

The myth states that many were Helena's suitors, but, advised by Odysseus, Tyndareus will respect Helena's decision in choosing a bridegroom and, if he was attacked, everyone should help him. Leda's daughter chooses Menelaus, brother of Agamemnon, as her husband, who, after the death of Tyndareus, ascends the Throne of Sparta.

“The curse of the descendants of Tantalus, once again, will be present in the history of the sons of Atreus. On a visit to Sparta, the son of Priam, king of Troy, Paris, also called Alexander, is enchanted by the beauty of the queen and, on his return to Troy, kidnaps Helen, taking her with him. Faced with such an offense, Menelaus asks his brother, Agamemnon, for help, who summons the other kings bound by oath to Menelaus and assembles the great fleet with the aim of avenging the kidnapping of Helen and attacking the city of Priam” (BRANDÃO, 2013) .

But the enterprise will not be an immediate success. At first, the omens were favorable to the Atridas (sons of Atreus). But Agamemnon's arrogance before Artemis, goddess of the hunt, will make the mark of Tantalus' descendants manifest once again.

At Aulis, Agamemnon goes hunting and, after killing a doe, claims that even Artemis could not have done better. The goddess is angry with Agamemnon. Once again, a Tantalid offends the goddess. The first was Atreus, who promised sacrifice to the goddess and retreated; now the king of Mycenae, with his arrogance. To appease the goddess's wrath and to gain victory against the Trojans, Agamemnon must sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia. When everything was ready, Artemis took pity on the girl and put a doe in her place, after having caused a darkness that had prevented the exchange from being seen, taking the king's daughter to Taurida to serve as a priestess. 2005; BRANDÃO, 2013).

Upon learning of her daughter's sacrifice, Clytemnestra plots revenge against her husband. Enter Aegisthus again, who had an affair with Agamemnon's wife. Once again, the Tantalids clash.

The drama of the house of the Atridas will be told, among many writers, by Aeschylus. In Orestia, we will find the saga divided into three pieces: Agamemnon, Coéphoras and Eumenides (ÉSQUILO, 2003). In Agamemnon, Aeschylus portrays the return of the King of the Argives after the victory over Troy. Clytemnestra, who was not satisfied with Iphigenia's sacrifice, had already plotted with Aegisthus her revenge against her husband by killing him.

But misfortune will not end with Agamemnon's death. The king's spirit would appear in a dream to Clytemnestra, haunting and cursing her. This one was to be killed by her own son, Orestes. This plot is found in the second play of Orestia: Coéforas.

“Orestes, still young, was sent by his sister Electra to Phocis, where he was brought up as a son by Strophius, married to Anaxibia, sister of Agamemnon. When he reached adulthood, Orestes was ordered by Apollo to avenge his father by killing his mother and Aegisthus. Arriving in Mycenae, he poses as an envoy of Strophius to announce the death of Clytemnestra's son, Orestes, himself in disguise. Such news brings comfort to Clytemnestra, who is freed from Agamemnon's curse. She sends word to Aegisthus. The latter, entering the palace, is brutally murdered by Orestes, who then, to be faithful to Apollo's mandate, kills his mother” (BRANDÃO, 2013).

In the third play, Eumenides, is the account of Orestes' flight to Athens by order of Apollo. The Erinyes, avenging entities, awakened by the spirit of Clytemnestra, reproach the protection given by Apollo to Orestes, demanding that he pay with his own blood. Desperate, Orestes embraces the effigy of the goddess Athena and asks her for her protection. Athena, hearing their cry, proposes a judgment, which will be accepted by the Erinyes. At the trial, there is a tie, with the goddess having the vote that she would break the tie. Athena votes in favor of Orestes, thus freeing him from the persecution of the Erinyes.

The story continues, as Athena's forgiveness frees Orestes only from the pursuit of the avenging entities. But what has already been demonstrated indicates what was said at the beginning of the section. Tantalus' hamartia inaugurates a chain of misfortunes that will befall his descendants, generating a series of new hamartiai, which marked those who had his blood, as well as all those who were involved with those of his house.

The theme of the consequences of Adam and Eve's sin in Christian theology

What in the first section we present as “hereditary misfortune” has points of contact with the “doctrine of original sin” of Christian theology. This is a very close reading of the Greek idea of a first act that causes consequences not only for the one who commits it, but for all his descendants.

In the Old Testament, the theme of the lack of the first human beings appears in Genesis 3: 1-24. In the myth of Adam and Eve, we see a shift from a state of grace, present in chapter 2 of Genesis, to a state of disgrace in chapter three. The sacred author will see in the sin of the first parents the cause of man's present condition.

Later, this theme will be elaborated by the apostle Paul (Rom 5,12-21), who will see in the “hamartia of Adam” the first cause of all that is “disgrace” in humanity. The Pauline Adam is more than an individual being, for in him all human nature is contained.

Based on Pauline thought, Augustine will develop his theology on “original sin”. This theology will take place in the face of the Pelagian heresy, which denied the need for infant baptism in view of its purification from the sin of the first Man, which would have passed on to all humanity. But it will be reworked by modern theology, which sees Adam not as a historical subject, but as a symbol of humanity.

The sin of Adam and Eve:

The account of the sin of the first parents is found in the third chapter of the book of Genesis. It follows on from the creation account contained in Gen 2,4:25b-2. In these two chapters, we understand how a situation of grace turns into a situation of disgrace for human beings. In Gen 2,7, we have the creation of the first man (Adam) from the dust of the ground (adamah) by God, breathing into him a breath of life (Gn 2,17); Then, God plants a garden and entrusts the care and cultivation of the garden to man, giving him the command, however, never to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil: “For in the day that you eat from it, you will die. ” (Gen 2,21:23). Given the command, God creates the woman from the rib of the man, in every way similar to the man, for she was created from his bones and his flesh (Gn 2-25). Creation knew a perfect balance, to the point that the book says: “They were naked, and they were not ashamed” (Gen XNUMX, XNUMX).

In the chapter that follows, we have a change in the human condition present in chapter 2. If, before, everything was in a state of original grace, now disgrace will befall not only human beings, but also all creation. The sacred author says that one of the creatures, the serpent, a cunning animal, served as an opponent of God's plans. She will be the very figure of temptation, when she tells the woman that there would be no problem eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, because what would really happen, if she ate, would not be death, but being equal to God: “God knows that in the day you eat it, your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Gen 3,4:5-3,6). Faced with this temptation, the woman not only eats the fruit of the forbidden tree, but also gives it to her husband (Gen XNUMX:XNUMX).

What interests us here is not just the act committed or the disobedience, but the consequences of this hamartia. The text says that, immediately after eating the fruit of the tree, man and woman realized that they were naked, were ashamed and made themselves garments of fig leaves (Gn 3,7:3,10); they also hid because they were “afraid” (Gn 3:12) and accused each other, fleeing responsibility for the act (Gn 13:XNUMX-XNUMX). If before there was balance, now there is an imbalance in the order of creation.

What follows the act of disobedience is a series of punishments. First, the serpent is cursed: “Because you have done this, cursed are you among all the domestic animals and all the wild animals. On your belly you will crawl and you will eat dust every day” (Gn 3,14) Then we have the punishment imposed on the woman: “I will multiply the sufferings of your pregnancy. In pain you will give birth to children. Your desire will go to your husband, and he will rule over you” (Gen 3,16:3). And finally, to man, God says: “Because you heard the voice of your wife and ate from the tree from which I commanded you not to eat, cursed be the ground because of you! With suffering you will feed on it all the days of your life... in the sweat of your face you will eat bread, until you return to the ground from which you were taken. For you are dust, and to dust you will return” (Gen 17:19-XNUMX).

In this way, we have a change of situation: from grace to misfortune, symbolized by nudity, fear, accusations, suffering, anguish, tiredness, breakdown of solidarity between man and woman, breakdown of solidarity between man and God, the impact on all creation and the greatest consequence: death. Thus, we can say that the so-called “sin of origins” will erupt evil in the world (LOPEZ, 2006).

Later, this theme will return with force in Pauline thought, in which the apostle will make the comparison between Adam, as the origin of sin and death, and Christ, as the one who brings us grace and saves us from this mortal condition.

Adam's sin in Paul:

In his theology on the human condition, the apostle will return to the first man of Genesis to identify in him the principle of death, suffering and sin itself, while presenting Christ in an antithetical relationship to Adam, as savior of the genus. human through grace. For Paul, the death of Christ reconciles the human race with God, and this reconciliation comes, above all, from God himself:

God proves his love to us by the fact that Christ died for us while we were still sinners. Much more now, that we are already justified by his blood, shall we be saved from wrath by him. If, when we were God's enemies, we were reconciled to him through the death of his Son, how much more now, being reconciled, shall we be saved through his life (Rom 5,8:10-XNUMX).

These verses serve as an introduction to the theme that follows: the fall of Adam and the grace of Christ. It can be seen that, in the above verses, the antithetical relationship between grace and sin is already found. Christ's death takes place “while we were still sinners”, meaning that such death is God's act of love for sinful humanity; once justified by the blood of Christ, a sign of God's love, we are “saved from wrath”, or from that which separates us from a relationship of friendship with God; in this way, in Christ, the enmity with God is annihilated and the human being finds Salvation. Paul recognizes that Christ's death on the Cross, his shed blood, reconciles and gives new life to humanity.

In the verses that follow, Paul will make clearer the salvific action of God in the human being through the antitheses Adam (one man) and Christ (one man):

As sin entered the world through one man and death through sin, so death spread to all mankind, because all sinned. Indeed, before the Law was given, there was already sin in the world, but sin cannot be imputed when there is no law. Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those who had not sinned after the transgression of Adam, who is a figure of him who was to come. However, the gift of grace is not like transgression. For if by the transgression of the one many died, much more did the grace of God abound to many in the grace of the one man, Jesus Christ. In the case of the gift, it is not as in the case of the sin of one: while the judgment of one is with a view to condemnation, the gift of grace from many transgressions is with a view to justification. For if death began to reign through the transgression of the one, much more will those who receive grace and the gift of righteousness through the one, Jesus Christ, reign in life. Therefore, as by the transgression of the one, condemnation was extended to all human beings, so by the act of righteousness of the one, justification that gives life was extended to all. For just as through the disobedience of the one many were made sinners, so through the obedience of the one many will be made righteous. As for the Law, it intervened to increase the transgression. But where sin increased, grace abounded all the more. Just as sin reigned in death, so grace also reigns through righteousness to eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord (Rom 5,12:21-XNUMX).

For the apostle Paul, Adam is not just a singular subject, but a “concrete universal”, because, for him, a single man, sin or disobedience generates implications that mark the entire humanity (death, condemnation, sin). Furthermore, according to Paul, we recognize sin in its consequences: “as sin reigned in death…” (Rom 5:21).

Christ, in turn, also presents himself as a “concrete universal of salvation”, because, through the grace of Christ, also one, signified in “obedience”, the human being achieves eternal life, justification and the own grace. According to Maldamé (2013, p. 57), this indicates that, for the apostle to the Gentiles, the human condition is universally marked by sin. Thus, in the face of this condition, human nature needs salvation.

However, from the texts cited, is it possible to say that the apostle recognizes in Adam's sin an "original sin" that is transmitted from generation to generation, as can be seen in the dogmatic formulation of "original sin"? In fact, when analyzing the text, it cannot be said that there is already in Paul a doctrine of original sin as we know it. What can be said is that the consequences of this sin are found not only in the human being, but in creation itself (Rm 8, 19-22) and that, what is transmitted, is death (Rm 5,12, XNUMX).

The impression we have is that Paul understands sin as a personification of evil, just as he personifies the Law, the Flesh, Death, Lack, Grace (MALDAMÉ, 2013; FREDRIKSEN, 2014).

The topic is controversial. What can be said, with certainty, is that Paul's intention, more than dealing with the subject of sin, is to show that there is a solution to the miserable condition in which humanity finds itself because of Adam's hamartia.

The concern of the letter to the Romans is to extol the universality of salvation, which is why Paul uses the figure of the patriarch of humanity. One must start from this perspective and, above all, not restrict Paul's intentions to the moral dimension. For Paul, what matters most is to manifest the universality of salvation and not to secure an idea of salvation dominated by the cosmology and history of his time (MALDAMÉ, 2013).

However, the whole of Pauline thought allows us to say that, for Paul, in Adam's hamartia is the hamartia of humanity. There is, in this sense, a solidarity between Adam and his descendants. However, there is even greater solidarity between humanity and Christ, for “where sin abounded, grace abounded all the more” (Rom 5,20:XNUMX).

Liberation from sin, which leads the human being to remain in a mortal state, makes that same human being experience a new life. In 1Cor 15,21:22-XNUMX, the Adam-Christ antithesis once again appears in Paul's thought: “For by a man came death, and by a man also comes the resurrection of the dead. As in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive.”

The sin of Adam in the thought of Augustine of Hippo:

Based on Pauline theology on Adam's peccatum and its implications for human nature, Augustine will elaborate his theology on what he calls "original sin".

It is not correct to say that the Bishop of Hippo will deal with the theme of Adam's sin only in the face of the Pelagian heresy, as he had already dealt with the subject on other occasions, mainly to refute the Manichean thesis that evil is integrated into human nature, since outside created from matter, which is evil. For Augustine, evil is moral, the fruit of human will, not natural (COSTA, 2002).

However, in fact, it will be in the face of the Pelagian heresy that Augustine will work the theme of the sin of the first man more closely. This is because a Breton monk, named Pelagius, appeared. Contrary to what was said, especially in the churches of North Africa, that baptism was necessary even for children, since these, even without personal sin, carried with them the stain of Adam's sin, Pelagius affirmed that the sin of Adam brought consequences only for Adam himself, and that human nature was already created mortal by God. Thus, bodily death is not the result of Adam's evil act, nor is Adam responsible for the death of all mankind; and, since death was not a consequence of the sin of the first man, but part of human existence itself, much less sin, or its mark, would be transmitted from generation to generation to all humanity (SESBOÜÉ, 2003).

For Augustine, the theses of Pelagius and his main disciples, Celestio and Julian of Eclanus, that human nature remains as it was created by God, without carrying with it the consequences of the sin of the first parents, go against what the apostle Paul teaches. The Bishop of Hippo substantiates his argument from Paul's letter to the Romans, as we can see:

“They [the Pelagians] say that the unbaptized child cannot be harmed by death, since he is born without sin. However, this is not what the Apostle, the Doctor of the Gentiles, says, through whom Christ spoke: Through one man sin entered the world, and death through sin, and in this way it spread to all men, in which all sinned” ( AUGUSTINE OF HIPPON, 1991).

However, it should be noted that the text used by Augustine diverges from the original text. The original Greek text of Romans 5,12:2003 says: “so death spread to all mankind (all men), because all sinned”; while the Latin translation that Augustine had in his hands does not, for the second time, contain the word death, saying only: “thus it passed to all men, in which all sinned”. Augustine will interpret that what happened to all men was not death, but Adam's own sin, in which all sinned, as if to say that sinful humanity sins in Adam's sin However, this interpretation is not correct, because we have a translation problem: first, the text used by Augustine has a flaw, as you can see; second, although it is a relative pronoun, the causal expression “eph'ô” could not have been translated by a relative pronoun “in quo”, relating it to “sin”, since, what Augustine interpreted as “ sin” (hamartia, feminine noun)” was actually “death” (Tanatos, masculine noun). Thus, it should be understood: “death passed to all men, because all sinned”, or “in which all sinned”, or even, “because all sinned” (SESBOÜÉ, XNUMX).

Augustine understands that there is solidarity on the part of all humanity in Adam’s sin, because he considers that in Adam all humanity was contained: “All sinned through that man’s ill will, because we were all one (omnes ille unus fuerunt), of whom all bring the original sin, of which he was voluntarily guilty” (AGOSTINHO DE HIPONA, 1985).

Although the fundamental text for understanding Augustinian theology on original sin is Rom 5,12:5,19, the bishop will support his thesis based on other texts of Scripture, such as Rom 50,7:XNUMX; or again in Psalm XNUMX:XNUMX:

Neither at the moment of conception nor birth do children have the will to sin; but the first man, in the very instant of his willful prevarication, committed an enormous sin, and by him human nature contracted the stain of original sin; and this is what the psalmist truly meant: “I was conceived in iniquity” (Ps 50,7) (AUGUSTINE DE HIPONA, 1985).

What Augustine is saying is: the man of today carries with him the sin of the first man, Adam. Because of this, it is necessary that, through baptism, man is washed not only from his personal guilt, but also, and especially from the guilt of Adam, the sin that we have inherited as children of Adam, the original sin (AUGUSTINE OF HIPPON, 1998).

Augustinian theology will find support in most churches of his time, especially among the Latin ones, and even later. The so-called “Pelagian heresy” will be condemned in, firstly, regional councils and synods, such as the Council of Carthage, in 418 (DENZINGER, 2013, art. 222-230); the 2nd Synod of Orange, in 529 (DENZINGER, 2013, art. 371-395); finally, in Trent, rescuing the definitions of these synods and regional councils, the doctrine of original sin was presented by a council of universal scope as an integral part of Catholic doctrine:

“If anyone asserts that Adam's transgression harmed him only, and did not spread to his offspring; who has lost for himself alone and not for us the holiness and justice received from God; or who, tainted by the sin of disobedience, transmitted to the whole human race “only death” and the punishments “of the body, and not also sin, which is the death of the soul”, let him be anathema; “For it contradicts what the Apostle said: “By one man sin entered the world, and death through sin, and thus death spread to all men, in that all sinned” (Rom 5,12:2013). […] If anyone denies that children should be baptized fresh out of the mother's womb, even if born of baptized parents, or else maintains that they are baptized for the remission of sins, but that they do not inherit from Adam any necessary original sin purify with the bath of regeneration to obtain eternal life; and, consequently, for them the form of baptism for the remission of sins should not be considered true, but false, be anathema” (DENZINGER, 1511, art. 1515-XNUMX).

The question of Adam's sin in current theology:

The theme of Adam's sin and his heredity had been dealt with by theology, it can be said, since Augustine formulated the doctrine of "original sin", transmitted by "generation". Even not using the term “generation”, but “propagation”, the Council of Trent confirms the Augustinian thesis and makes it a “dogma of faith”.

However, it is important to consider the fact that both Augustine, his predecessors and those who used his thought to support the idea of massa damnata believed that the biblical Adam was a historical subject, the first of human beings and in him was contained. all humanity (LADARIA, 1998).

With the advancement of exegetical science, biblical archeology and the new discoveries about the origin of the human being and its evolution, theology found itself in the need to reinterpret the theme of Adam's sin without emptying the dogmatic sense, however, considering at the same time its mythical aspect. One could no longer sustain the idea of a primordial man, patriarch of humanity, to whom the current condition of the human being is due. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that the whole of humanity enjoys universal solidarity with regard to its own fragility. Evil, suffering, sin and death are universal and individual realities. In this sense, Adam is no longer seen as a historical subject and is considered based on his function. Adam comes to be seen as a symbol of the mediation between God and humanity. God wants the human being to become more and more his “image” from the very condition of “human”. Instead, man removes this grace from himself with a “no” to God, giving rise to the history of sin (DE LA PEÑA, 1991).

Therefore, the historical meaning of the character “Adam” is removed, understanding him as a symbolic subject. Adam's sin is the sin of Humanity, of each and every one, supported by free will. As stated by Sesboüé (2003):

The narrative of the creation and the lack of Adam has the function of unfolding the origin of evil in relation to good. It expresses, in the religious language of the myth and, therefore, of the symbol, an event of 'original' freedom, the passage from innocent but fallible man to sinful man. The human limit linked to the state of being was experienced as a prohibition and provoked a revolt.

Thus, the originality of sin is not in a historical figure, but in what the mythical figure “Adam” represents: the limited condition of the human being as a creature, who desires something more, which does not belong to his reality and, therefore, freely , revolts. Therefore, sin cannot be understood only as personal or individual, but universal or social. There is, therefore, a universal solidarity of all human beings, of all times, in their limited condition as creatures. De la Peña (1991) states:

“This interpersonal solidarity in sin implies a sort of reciprocity: I am a passive and active subject of it and as I cannot blame either God or human nature for the origin of its dynamic power, I have to think of the human factor as an activating element of the process ( “originating” sin). As a result of this factor, the mediating function of grace, foreseen by God in the first instance and required by my constitutive sociability, was frustrated, and a breach opened up between God and man that man, by himself, cannot repair, but only enlarge (originating sin).

In this way, it is understood that there is no heredity, but solidarity in sin. “Personal sin” presupposes and, at the same time, actualizes the “originating” and “originating” sin that is perceived in the sinful condition of human beings, the fruit of their freedom. It can be seen, therefore, that the doctrine of original sin shows the tension between “previous destiny” and “personal responsibility” that is found in the letter to the Romans and that “is nothing but a reflection of the tension between being social and being personal” that defines and constitutes man, and to which current anthropology is extremely sensitive” (DE LA PEÑA, 1991)

Still, in current theology, the effects of Christ's grace in the face of original sin stand out more. As stated by Ladaria, “we cannot consider the doctrine of original sin something “prior” to Christology and soteriology… Only with regard to Jesus' salvation does it make sense to ask ourselves what Christ frees us from” (LADARIA, 1998). It is considered that, contrary to what was said in Augustinian theology, the head of humanity is not Adam, but Christ. Humanity's first solidarity is not with fallen man, but with Christ. That is why “all are called to be one in Jesus and to cooperate in carrying out this plan” (LADARIA, 1998). This solidarity is also universal, for “all humanity was reconciled to God through Christ, not just individual sinners” (LADARIA, 1998)

Conclusion:

After this reflection on the myths of Tantalus and of Adam and Eve and their consequences, we can see that the theme of the human condition is common in “mythical literature”. In this article, we chose these two myths, but several could have been dealt with, since every religion has a founding myth, which speaks of its gods, the human condition and its future on earth. The proposal, from the beginning, was not to confuse the myths, in the sense of wanting to find in one the other, but to find points of convergence and even of divergence, thus enabling dialogue. Therefore, in this dialogue, we also chose to work with the religious discourse from the point of view of anthropology, since “if everything human is of interest to literature, the same is true of the religious domain of man” (MANZATTO, 1994).

In this sense, the theology of the Greeks sought in the myth of Tantalus, but not only in it, as we saw at the beginning of this article, situations that explain not only suffering, but also the idea of a curse that passes between generations, identifying a solidarity between generations in suffering.

The myth of Adam and Eve was also, for Christian theology, a reference for working on the issues of evil, suffering and death present in human reality. The myth wanted to symbolize man's dissatisfaction with being what he really is, giving rise to a series of evils and imbalances in his relationships with God, with nature and with each other. The so-called “Sin of Adam” or “Original Sin” ends up identifying a solidarity existing between all human beings in their limited condition as creatures, causing revolt. To live in grace, in this sense, is to fully live your humanity, recognizing yourself as a creature in dialogue with the creator. “Disgrace”, in turn, is the disorder of relationships that prevent us from living the fullness of the human “being”, seeking to “be” something else. The grace of Christ, in this sense, is what restores the balance of the relationship between God and the human being, between the human community and between men and all creation, because, in Christ, “it pleased God to make all the Fullness inhabit. and to reconcile all beings through him and for him, on earth and in heaven, making peace through the blood of his cross” (Eph 1,19:XNUMX).

You may also like

- Analyze What Repentance Is Before God

- Find your freedom with Toltec philosophy

- Try the 7 Steps to Forgive Others

Finally, I hope I could have helped my reader friend to understand such an important topic in the field of philosophical knowledge.